The

previous essays can be found if you click on the links below.

|

| Victor Perkins |

Victor Perkins was

a key critic for Movie magazine, one of the main forums for the auteur

theory debates of the early to mid sixties and beyond. Although himself 'a

believer', in 1990 Perkins criticised auteurism and the auteurists “for

making a crucial error in their exaggerated concern with continuities and

coherence across the body of a director's work.” Cahiers critics denied

auteur status to certain directors seen to be stylists if their films were

otherwise lacking overall coherence. It

was this absolute insistence on continuity or what Perkins called “the

repetition of the “author-code traced from film to film” that he saw as

distorting proper acknowledgement of other views on the creative role of the

director thus overriding the achievement, in a single film, of expressive

values such as “economy, eloquence, unity, subtlety, depth and vigour” that

might be attached to the single work but not necessarily to a multiplicity of

works attributed to the director. In other words “what a director does well is

at least as important as what he does often.” Rather than just an observation

that an “auteur's” work could additionally display striking continuities and

coherent development it was transformed into a test of authorship.

Andrew Sarris referred to the auteur theory as 'pattern' theory. “Only after thousands

of films have been evaluated will any personal pantheon,” he asserted, “have a

reasonably objective validity.” Contending “that single films matter not that

much,” he refers to Jean Renoir's observation “that a director spends his life

on variations of the same film.” It does suggest that outside the pantheon,

Sarris's 'pattern' is a measure of the degree to which two hundred or so

directors outside the pantheon most often working on assignment under studio

contracts, fell short of realising auteur status, achievement in individual works notwithstanding.

Central to the

studio system was the assigning of a script to a contract director, together

with a studio producer to oversee the production and frequently with the lead

actor(s) already cast and key technicians allocated. This gave rise amongst some auteurist critics

to the notion of the metteur-en-scène (literally 'the director' but here

given added connotation) to cover the case of the director who maintained some

continuity of style through a number of assignments almost always in more than

one genre, but not of theme which came with each script more or less as a

given. Metteurs en scene were thus seen to occupy the middle ground between

auteur and superior craftsman.

Sam Rohdie defines

a 'frontline' auteur in the pantheon as “someone who creates his or her own

system” (a dialectic of style and subject) “rather than merely bringing an

existing system into play” (with at best only minor variations in plot and

characterisation) in an established genre.

Paradigm cases

leading to debate on the status of a director (auteur or metteur en scene?) in

the early-mid fifties at Cahiers, were at that time Vincente Minnelli

and Otto Preminger to whom might be added others whom I designated as possible second and

third line auteurs such as George Cukor, Mitchell Leisen, Charles Walters,

Stanley Donen, Jacques Turner and arguably Gerd Oswald. The notion of the

metteur-en-scène seems to have originated amongst the Cahiers critics, a

notable example being Jacques Rivette's adamant rejection of Minnelli for

auteur status as he was “always subordinating his talent (as a stylist) to

someone else” (1). Such deployment of the notion was never seriously taken up

by the Movie critics who actually implicitly rejected it by claiming

that Minnelli's style was his meaning, or Andrew Sarris who, while suggesting

that Minnelli believed “more in beauty than in art,” seemed to recognise

his auteur credentials by placing his oeuvre along with those of 19 other

directors in the “far side of paradise” category next to the pantheon. The case

for Minnelli as auteur has subsequently been persuasively articulated by Thomas

Elsaesser but in terms other than simple thematic coherence (See Part 9).

In any case the

idea of the metteur en scène did not survive the passing of the studio

system, the assignment of films by the front office to creative staff, most of

whom were under medium to long term contract with their status being their only

negotiable leverage. Even most 'A' list directors at some stage were obliged to

take on major projects at short notice, a more commonplace occurrence with

directors further down the hierarchy. Mostly 'A' directors were involved in

projects from their inception so that when the system was falling apart in the

late sixties and into the seventies, directors like Minnelli and Cukor tended

to drift into relative inactivity and had to look outside the studios for work;

Cukor directed only four films after My Fair Lady,1966-81, Minnelli two

in the decade 1966-76

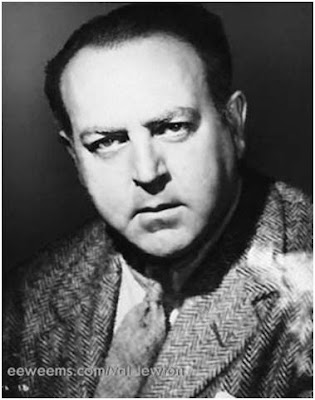

Jacques

Tourneur: “journeyman” auteur or metteur en scène?

|

| Jacques Tourneur |

Jacques was the son

of Maurice Tourneur, an emigré pioneer of pictorial invention in Hollywood

silent cinema who returned to France to direct films in the thirties. Jacques

acted as his assistant and directed four feature films in France before himself

returning to Hollywood in 1936, directing a series of short films at MGM before

moving into 'B' features on assignment. He then teamed up with innovative

producer Val Lewton at RKO in 1943 to direct three classic horror films Cat

People, I Walked with a Zombie and The Leopard Man, imaginatively

realised on low budgets. Tourneur seemed to be speaking with the voice of a

'journeyman' when he said that in Hollywood, he “accepted systematically”

scripts that were offered to him “regardless of what the scripts were about”

(2) He then qualified this by saying that he saw every script as an opportunity

“to see what can be done with it” in the process discovering his own

sensibilities “doing the best” with what he was given, letting his “unconscious

do the work.”

|

| Unwanted, the demon visualised in Night of the Demon |

The only two films

he initiated (I Walked with a Zombie and Stars in my Crown) are

counted with Canyon Passage, Out of the Past and Night of the

Demon as his most fully realised films. His three horror films made with

Val Lewton and Night of the Demon are widely recognised as

testing the conventions of the genre with “the unrevealed horror of the

everyday” - he hated the expression 'horror film'; the producer insisted on

visualising the Demon in post-production very much against Tourneur's

wishes. He was a believer in the power of a felt but unseen force which imbues

his best work.

The 'testing of his

sensibilities' Tourneur carried over into other genres. In ranking, they

closely follow the above five key films : Experiment Perilous, Anne of the

Indies, Wichita, Great Day in the Morning and Nightfall, all

seriously original in their personal approach to their respective American

genres. His most personal film and widely regarded as his best, Stars in my Crown, is a moving piece of Americana on the dark side.

At the other end of the spectrum, given his position in the industry, there were inevitably some assignments he could do little with beyond delivering efficient medium to low budget entertainments - his first four features at MGM (1939-41), Days of Glory (44), Flame and the Arrow (50) Circle of Danger (51) - and his last five features from The Fearmakers (58) to City Under the Sea (65), his work then in steep decline, marred by lack of suitable opportunites.

At the other end of the spectrum, given his position in the industry, there were inevitably some assignments he could do little with beyond delivering efficient medium to low budget entertainments - his first four features at MGM (1939-41), Days of Glory (44), Flame and the Arrow (50) Circle of Danger (51) - and his last five features from The Fearmakers (58) to City Under the Sea (65), his work then in steep decline, marred by lack of suitable opportunites.

Tourneur had an

outsider's analytic eye for ambiguities in the playing out of social and

spiritual values which would have otherwise in all probability rested largely

undisturbed between the lines in conventional scripts of widely varying quality

assigned to him. He uncovered or inserted subtleties and ambiguities he found

in the stories primarily through his mise en scène - a finely tuned ability to

create atmosphere evident early on in the Lewton horror films, a subtly

nuanced sensibility in visual style and tempo of performance (a

“quietism”) carried over into other genres. He regarded the lighting of

utmost importance placing priority on the establishing of natural light

sources. Tourneur did not impose himself

upon the actors other than encouraging them to lower their voices giving their

sentences “a less dramatic rhythm.” As

masters of low key nuanced performance, Joel McCrea and Dana Andrews were his

ideal leads.

On the face of it, with style so paramount, Tourneur might still seem

to some to best fit the status of a stylist without a recurring theme – that of

metteur en scène. While a director of

interest, he was not in the select band of cause célèbres taken up by

the Cahiers critics in the fifties whose auteurism lacked Sarris's

overall concern with constructed pattern theory. Tourneur's work as an auteur was appreciated

by a rival journal Présence du Cinéma and by pre-eminent

critics such as Jacques Lourcelles,

Louis Skorecki, Bertrand Tavernier, Gérard Legrand and Jean-Claude Biette.

|

| Frances Dee, Edith Barrett, Jeni Le Gon, I Walked with a Zombie |

Of the 29 features

Tourneur completed after returning to Hollywood, 12 amount to little more than

the work of a competent craftsman, with a further 7, while less distinctive

works, each make a significant contribution to the overall coherence of his

oeuvre. It is the 10 key works listed above, beginning with I Walked with a

Zombie, that are each an example of the general proposition put by Victor

Perkins (see above), of a theory of authorship anchored in the prior value of

individual works that “might usefully set out to explain why so many directors

who have achieved authority (through a

structure of anchored moments) turn out to have done so repeatedly – and often

in strikingly coherent terms.” The same down-grading of the priority of

recurrence can be said to be necessary in the assessment of the authorship

status of the other 30 directors, at least, in the 'second line' as I have

listed in Part 9.

Gerd Oswald :

auteur, metteur en scène or superior craftsman?

|

| Gerd Oswald |

Gerd Oswald, the

son of successful German film director Richard Oswald emigrated to America with

his father in the late thirties and directed his first and most widely praised

film, A Kiss Before Dying in 1956

Oswald directed

seven features in Hollywood from 1956-8, only six of which need concern us

here: two low budget westerns (The Brass Legend, Fury at Showdown),

a film noir (Crime of Passion) and three dramas centred on perverse

psychology (A Kiss Before Dying, Valerie and Screaming Mimi).

The interest in the two westerns is not primarily thematic – they follow fairly

familiar B western plots – one revolving around revenge and corruption in a

small town, the other a lawman's struggle to bring a bad man to justice. At the

time unnoticed by the critics on the lower half of double bills, what lifts

these two films out of the ordinary and invests them with special intensity, is

Oswald's commitment to his craft (and

that of his cinematographers Charles van Eager and Joseph LaShelle), working on

7 and 5 day shooting schedules respectively deploying the tracking camera,

depth of field, lighting and unobtrusively effective camera placement to invest

the films with a special intensity. (3).

|

| Sterling Hayden, Barbara Stanwyck, Crime of Passion |

The entry for

Crime of Passion in Silver and Ward's Film Noir Encyclopedia suggests

that it is representative of the shift of noir mood from romantic

fatalism and into “suburban disquietitude” which, in the early to mid-fifties,

here involved a couple in attempted corruption of the promotion process leading

to unpremeditated murder. Sterling Hayden is a detective in the San Francisco

PD with limited prospects of promotion and Stanwyck, a formerly successful

newspaper columnist who quickly becomes disillusioned with married life in

suburbia. Shadowy suburban interiors at night marked a trend to

non-expressionistic lower key lighting and, consistent with Oswald’s other

films, a relatively spare use of reverse angle editing in favour of arranging

figures in the frame. At several points the more naturalistic style is

punctuated with a montage of faces with the music score subjectively expressive

of Stanwyck's sense of alienation.

There is also a

sense of disquietude in A Kiss Before Dying but here bathed in

the bright sunlight and pastel interiors of the South West in long takes with

minimal reverse angle shots in concert with the Scope screen as a young

psychopath (Robert Wagner) coldly plans and commits the murder of his pregnant

girlfriend (Joanne Woodward) and then continues his life of manipulation and

murder as though nothing has happened.

|

| Anita Ekberg, Valerie |

While in a western setting, Valerie has

been referred to as 'a frontier Rashomon' in the confrontation with

conflicting accounts of the film's opening incident off-screen involving murder

and attempted murder of the family and wife (Anita Ekberg) of an army veteran

(Sterling Hayden) and ranch owner who

was employed to torture prisoners during the Civil War. Again, as in the other

westerns, Oswald uses relatively long takes which Sarris finds have “a fluency

of camera movement (that) is controlled by sliding turns and harsh stops

befitting a cinema of bitter ambiguity.” Ekberg is also a victim in Screaming

Mimi, suffering a nervous breakdown after being sexually assaulted, taking

a job as a stripper and ending up on the couch of a psychiatrist of dubious

reputation although according to Paul Taylor in Time Out “Oswald fails

to inject this provocative scenario with the same eerie imagination that

fuelled A Kiss Before Dying.”

|

| Brainwashed poster |

Sarris seemed

anxious to anoint Oswald as an auteur for “his success in imposing a personal

style.” In 1961 in Germany Oswald directed and co-scripted an anti-Nazi drama Brainwashed/The

Royal Game starring Curt Jurgens and Claire Bloom, based on a novella by

Stefan Zweig, presumably as a contribution to postwar de-Nazification. In Oswald's Hollywood films Sarris finds “paranoiac overtones,” and considers that

“anti-Nazi symbolism is not too hard to detect” in the six films referred to

above. Other than perhaps for A Kiss before Dying which is based on an

Ira Levin thriller, the evidence of Oswald's authorship, the unity of

style and theme, is inconclusive when compared to Tourneur's key films. It is

sufficiently thin to bring the recurrence question discussed above into play. A Kiss

Before Dying, Valerie and Crime of Passion do not per se lift

Oswald from metteur en scene to auteur which does not diminish, so long

unnoticed, what he did achieve with skill and commitment, given such modest

resources, in several of these films.

1. Since the posting of the essay on Minnelli I have found that he is on

record as saying that he nearly always had the opportunity to work with the

writer “more or less from the beginning... often for five or six weeks if the

script had not been completed.” He pointed out that “The Bad and the

Beautiful had an entirely different connotation in the original script,

which was simply about a man (the producer played by Kirk Douglas) who was more

or less of a villain.”

2. In principle if not entirely in practice – Tourneur turned down The

Furies subsequently directed by Anthony Mann and The Set Up by

Robert Wise.

3. These key films are all on the dark side. Oswald also directed Paris

Holiday (1958), a farcical comedy starring Bob Hope (who also produced) and

Fernandel with Preston Sturges making a very brief appearance. More successful

critically was another comedy, Bunny O'Hare (1971), Oswald's last film

in Hollywood, with Bette Davis and Ernest Borgnine. He also directed episodes

of a number of TV series including Star Trek and “a visually arresting and thematically over

the top” episode of Outer Limits titled “Shape of Things Unknown.”

Note: Fury at Showdown and Crime of Passion are free to view on

YouTube.

Acknowledgment to

Chris Fujiwara for his comprehensively detailed auteurist study of Tourneur's

cinema in Jacques Tourneur the cinema of nightfall 1998. Also

recommended is a short essay on Tourneur by Barrett Hodsdon in The Elusive

Auteur 2017 pp 148-151. See other sources in Part 10 .

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.