Robert and Raymond

Hakim produced three of Julien Duvivier’s films. Their reputation as producers

is a little up and down. I first noticed this when I did some notes on Joseph

Losey’s Eva (France/Italy, 1962)

which were included as a booklet with the Australian release of the film on DVD

by Madman. Losey had vilified the Hakims unmercifully after his film was

continually cut and re-cut by the producers following unsuccessful previews.

The Hakims

made three films with Duvivier as director, strung out over a quarter of a

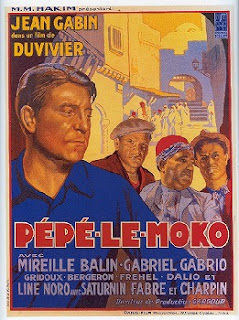

century. The first of them Pepe le Moko (France,

1937) was one of the director’s, and producers’, greatest successes. In a short

online note

about the Hakims, John Baxter says: After working for Paramount in Paris, the Egypt-born Hakim brothers became

independent producers in 1934, financing Duvivier's Pépé le Moko and

Renoir's La Bête Humaine. These sensational and discreetly salacious

films by directors who, though well-established, were slightly out of the

mainstream, established a strategy that would help the Hakims survive French

cinema's most disastrous decades.

The Hakims

made three films with Duvivier as director, strung out over a quarter of a

century. The first of them Pepe le Moko (France,

1937) was one of the director’s, and producers’, greatest successes. In a short

online note

about the Hakims, John Baxter says: After working for Paramount in Paris, the Egypt-born Hakim brothers became

independent producers in 1934, financing Duvivier's Pépé le Moko and

Renoir's La Bête Humaine. These sensational and discreetly salacious

films by directors who, though well-established, were slightly out of the

mainstream, established a strategy that would help the Hakims survive French

cinema's most disastrous decades.

Over the years the Hakims made a success of

producing some of the major European movies of the day. They also relocated to

America for awhile and produced Renoir’s The

Southerner and a remake of their

production of Carne’s Le Jour se Leve, The

Long Night (Anatole Litvak). They produced two of Antonioni’s greatest

films L’Aventurra and L’Eclisse and three of Claude Chabrol’s early New Wave

movies.

Pot-Bouille (France, 1957) is an adaptation of Zola’s novel of the same name. (Duvivier had in 1930 adapted the author’s Au Bonheur des Dames.) In many ways it represents a peak moment in the cinema de papa of the day. Meticulously filmed almost entirely on gleaming and somewhat inauthentic studio sets, everything glistens, everything is polished including the telephoned in performance of Gerard Philippe in the lead. It was the sort of film that no doubt had the young men of the New Wave gnashing their teeth in frustration. (Of course only a few years before Duvivier made his best film of the 50s, the Simenon-like twisting tale of betrayal, male guilt and amour fou, Voici Le Temps des Assassins.)

Pot-Bouille (France, 1957) is an adaptation of Zola’s novel of the same name. (Duvivier had in 1930 adapted the author’s Au Bonheur des Dames.) In many ways it represents a peak moment in the cinema de papa of the day. Meticulously filmed almost entirely on gleaming and somewhat inauthentic studio sets, everything glistens, everything is polished including the telephoned in performance of Gerard Philippe in the lead. It was the sort of film that no doubt had the young men of the New Wave gnashing their teeth in frustration. (Of course only a few years before Duvivier made his best film of the 50s, the Simenon-like twisting tale of betrayal, male guilt and amour fou, Voici Le Temps des Assassins.)

Finally there

is Chair de Poule (France, 1963), an

adaptation of James M Cain’s “The Postman Always Rings Twice”, a book already

filmed by Tay Garnett and, without authorization, by Luchino Visconti. John

Baxter sums up the Hakims’ approach at this time Throughout

the 1960s, the Hakims seldom deviated from the style of film successful for

them in the 1930s: star-driven melodramas with plenty of sex, and an international

market built in. The recipe that launched Simone Signoret in Casque d'or

proved equally serviceable for Alain Delon in René Clément's Plein

Soleil , Roger Vadim's remake of La Ronde , Luis Buñuel's Belle

de jour and Karel Reisz's Isadora . All shrewdly exploited the

European cinema's reputation for sophisticated sensuality without surrendering

totally to the mass market.

Baxter doesn’t even mention Chair de Poule, possibly the most unprepossessing movie made by the brothers during this late period of their, and the director’s, work.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.