Editor's Note: John Baxter is an Australian-born, writer, film-maker, critic and biographer. His published books range across fiction, biography, history and, on many occasions, volumes devoted to his adopted city Paris, where he has lived since 1989. OF LOVE AND PARIS is published by Museyon in New York. The book has an introduction followed by 32 chapters devoted to what the author describes as 'some of the ways men and women have used their lives to define and enlarge the concept of Love. That all did so, at least in part, in Paris was no coincidence."_ Australian readers may obtain a copy from the online bookseller BOOKTOPIA

*************************

Twenty-year-old actress Jean Seberg met author and diplomat Romain Gary in 1961. Twenty-four years her senior, he was the French Consul in Los Angeles. Within a few months, they were sharing an apartment on the Ile St Louis in Paris, where Seberg, after a false start in Hollywood, had just enjoyed her first success in Jean-Luc Godard’s À Bout de Souffle/Breathless. Her portrayal of the free-living American girl who sells copies of the Herald Tribune on the Champs-Élysées and becomes involved with gangster fantasist Jean-Paul Belmondo made her an icon overnight, inspiring François Truffaut to call her “the best actress in Europe.”

But Seberg’s confidence never recovered from her experience with the tyrannical Otto Preminger, who directed her first two films, Saint Joan and Bonjour Tristesse. Subsequent roles exploited her gamine charm but exposed a meagre talent.“I am the greatest example of a very real fact,” she confessed, “that all the publicity in the world will not make you a movie star if you are not also an actress.”

Romain Gary, loud, bearded and glowering, trailing a reputation as resistance fighter and novelist, re-made himself repeatedly, playing what one critic called a "picaresque game of multiple identities.” Writing at various times as Fosco Sinibaldi and Chatan Bogat, and claiming to be the son of Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine, he was actually born Roman Kacew in Lithuania. “Fluent in six languages,” wrote cultural critic Adam Gopnik, “he passed punningly from one to the other in a dazzling display of instinctive interlineation.”

At the fall of France in 1940 he left the diplomatic service to join Charles de Gaulle’s exile government in London, and flew in bombers with the Free French. While in Britain, he changed his surname to Gary. “ ‘Gari’ in Russian means ‘burn!’,” he explained. “I want to test myself, a trial by fire.” After the war he resumed his career as a novelist. His 1956 Les Racines du Ciel/The Roots of Heaven articulated a compulsion to live always on his own terms. Its main character, confined in a German prison camp, hallucinates about the elephant as a symbol of freedom and, on his release, devotes himself to saving them from extinction. “Think about elephants riding free through Africa,” he says. “Hundreds and hundreds of wonderful animals that no walls nor barbed wire can contain, crossing vast spaces and crushing everything in their path, with nothing able to stop them. What freedom!” The Roots of Heaven was awarded France’s most prestigious literary prize, the Prix Goncourt, which no writer can win more than once, a rule Gary took as a challenge. In 1975, when Émile Ajar won for La Vie Avant Soi/The Life Ahead, Gary revealed with glee that the book was his, and the man giving interviews as Ajar his cousin.

In Paris, Gary held court in fashionable Brasserie Lipp and was a familiar face on television, often in spirited defence of President de Gaulle, whom he continued to admire once he became president. When the Quai d’Orsay handed him the plum posting to Los Angeles, perhaps in recognition of that support, his wife, writer Lesley Blanch, declined to join him, so Gary, abandoning both her and his “official mistress,” British novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard, went alone. Once installed in the consulate, with his secretary as paramour, he rented a separate apartment as a writing retreat and love nest for his many affairs, culminating in that with Seberg.

Gary and Seberg became a golden couple. They dined with the Kennedys and lunched with de Gaulle. Seberg used her celebrity to campaign for social causes. On a flight from Paris to Los Angeles in 1968, she met Allan Donaldson who, as Hakim Jamal, led the Organization of African-American Unity, a splinter group of the Black Panthers. As they parted, Seberg created a furore by giving the Panthers’ raised-fist salute in full view of the press. In 1969 she hosted a Hollywood fund-raiser for the group, attended by Jane Fonda, Vanessa Redgrave, Paul Newman and other engagé personalities. She and Donaldson also became lovers.

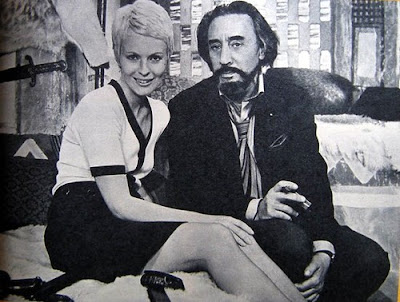

Dissatisfied with the films made from his books, Gary decided to direct one himself, and shot Birds in Peru with Seberg in the starring role (above). “Oh yes, she has a lovely face,” critic Roger Ebert wrote of her less-than-inspired performance. “We see it for minutes on end in Birds in Peru. Looking up at us, down at us, away, in profile, turning toward, blank, fearful, seductive, nihilistic. It would almost seem that the face was Romain Gary's reason for making the movie.” While on location, Seberg began an affair with Carlos Navarra, described as “a Third World adventurer”. Shortly after, on the musical Paint Your Wagon, she also shared the bed of co-star Clint Eastwood. Furious and humiliated at this news, Gary challenged Eastwood to a duel and booked a flight to the film’s location in Baker, Oregon. The actor fled back to Los Angeles and Gary sued for divorce.

Seberg became pregnant by Navarra following Paint Your Wagon. Meanwhile, her political activism attracted the attention of the FBI which targeted her in a smear campaign, leaking news of her pregnancy to the Los Angeles Times and implying that a Black Panther was the father. Seberg attempted suicide, inducing the premature birth of a daughter, who died two days later. Gary loyally announced the child was his, and arranged for the body to be displayed in an open coffin, showing she was white.

Seberg would never recover from the death of her child. Abusing alcohol and amphetamines, she suffered periods of depression, and made a number of suicide attempts, often on the anniversary of her daughter’s death. In response, Gary wrote Chien Blanc/White Dog, parodying Hollywood personalities who embraced fashionable political causes and attacking the cynical activists who exploited them.

In 1972, Seberg married Dennis Berry, film-maker and son of blacklisted director John Berry, with whom she became further involved in radical politics. François Truffaut tried to cast her to type as the troubled English actress in La Nuit Americain/Day For Night, his celebration of film-making, but she ignored his approaches, and the role went to Jacqueline Bisset. Her downward spiral continued. She started divorce proceedings against Berry but before they were complete entered a bigamous marriage with Ahmed Hasni, described as “an Algerian mythomaniac linked to drug trafficking.”

In 1979, Seberg went to Guyana to shoot La Légion saute sur Kolwezi but was too strung out to work and had to be replaced by Mimsy Farmer. It was the last hope of reviving her film career. On her return to Paris, she once more attempted suicide, this time by throwing herself in front of a Metro train. In August of that year, Hasni reported that she had wandered away from their home, drugged and dazed by the heat, carrying a bottle of water, and naked except for a blanket. Police found her nearby ten days later, dead from an amphetamine overdose in the back of her car.

Her death left Romain Gary profoundly depressed. The following December, he lunched with his publisher, then returned to the apartment on rue du Bac he had shared with Seberg, and shot himself. His suicide note, headed "For the press", began “D-Day. Nothing to do with Jean Seberg. Devotees of the broken heart are requested to look elsewhere...So why?... I have at last said all I have to say.” Few were convinced. “Both died by their own hands,” wrote Adam Gopnik of this star-crossed couple, “though in a way each died by the other’s.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.