Like most cinephiles I regarded viewing The Other Side of the Wind(Orson Welles, 2018) almost with a sense of religious obligation. The enormously long period of time from initial production to final release (for which we must be ever thankful to Netflix) is known to pretty much everyone. That long and convoluted history is readily available on Wikipedia and there are bountiful reviews. So I don't propose to deal with either of these issues further.

The storyline is so intensely autobiographical: a wellworn and previously ultra famous film director returns from Europe to America with an unfinished project "in the can" with the intention of finding backers. He fails in this and the culminating scene is his death by motor traffic accident. My interest in this subject was the extent to which Mr Welles had found some insight into his lifelong (at least as a director) difficulty, if not complete unwillingness, to complete projects. The film as shown certainly displays the director as factually being unable to complete at least this project, but it certainly doesn't seem to indicate to me any understanding of why this was such a continuing problem.

Some light on this I think can be found in an interesting article by former actor and long-time director Jonathan Lynn in the Times Literary Supplement, November 23, 2018, "Orson's bag". While this is a personal account of a middle-aged man when he was young and very much in awe of Mr Welles it describes certain stages in the project. Most relevant in my view is that throughout the production Mr Welles resided full-time at the Cipriani hotel in Venice or at the sister hotel the Villa Cipriani. For at least part of the time it would appear that the entire crew was also staying at the Villa Cipriani. These are among the most expensive hotels on earth and I feel that just Mr Welles' residing there, much less his crew, might have been enough in and of itself to make a film.

It certainly would have added an extra gloss to a film like Chimes at Midnight (Orson Welles, 1965) a film that whatever its other qualities always looks "cheap as chips". In this I think is the answer to the question I posed to myself. I don't think Welles had any intention of finishing most of his projects. A project shoot was theatre in itself and was the apparent vehicle to provide for his luxurious if peripatetic lifestyle.

|

| John Huston as JJ Hannaford, The Other Side of the Wind |

I wish to examine this in greater detail but I also accept, upfront, that the connections I draw may not be to everyone's satisfaction. I wish to dwell on the relationship between the director of the film within the film played by John Huston (JJ Hannaford) and his then protégé Brooks Otterlake (Peter Bogdanovich). The relationship in the film, as well as the film within the film reflect on the real-life relationship between Mr Welles and Mr Bogdanovich. At the very beginning of shooting, Mr Bogdanovich was amongst the most praised directors of his generation. I well remember as a very young person indeed going to see The Last Picture Show(Peter Bogdanovich, 1971) and it is still my view that although a "small" film, it is just about perfect, not only in purely cinematic terms but as a recreation of one of the finest American novels of the 20th century, "The Last Picture Show” by Larry McMurtry (1966). Yet like his hero Mr Welles, Bogdanovich began to fall seriously from favour quite soon. This has often been attributed to the breakup of his relationship with his creative partner and wife Polly Platt. As Mr Bogdanovich's production designer, her influence was extraordinarily significant and this can be judged by the falling away in quality of Mr Bogdanovich's films after their divorce.

|

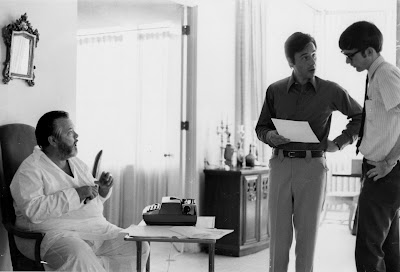

| Welles, Peter Bogdanovich, Joseph McBride during the shooting of The Other Side of Wind |

In the current film under review, he plays Brooks Otterlake which on momentary reflection is a watery connection taken too far. There is a character in the satirical novel by Evelyn Waugh "Vile Bodies" (1930), Lord Monomark. This character was originally intended to be Lord Ottecove and the name as well as the ebullient and extremely flashy character is clearly a reference to the famous Canadian- British industrialist and newspaper proprietor, Lord Beaverbrook. The name change came at the insistence of the publisher' s lawyers. I think there is more than a coincidence here. Otterlake, formerly a disciple of the director has now become a creative power in his own right with all the appearances of a prior wealth which Welles too enjoyed as a youth, but lost. And the references also to a foreign source of wealth: Canada. In the case of Mr Bogdanovich's background, his father was a Serbian pianist of very considerable repute and his mother an heiress to a very substantial Austrian Jewish enterprise.

So far as I'm aware, although both parents arrived in America as refugees in 1939, they were persons of substantial means and this is evident in the education and early life of Mr Bogdanovich. It's well documented that he spent numbers of years looking at upwards of 400 films per year. So was their time for ‘work’; instead rely upon the family fortune.

Reviews of the film, as between director and Otterlake, as well as commentary on the relationship between Mr Welles and Mr Bogdanovich make note of the incipient jealousy between them. Mostly the comments are of an artistic kind: Mr Welles in decline having first had a "disciple" and Mr Bogdanovich very much in the ascendant. However, I see the relationship, while certainly of envy, as basically financial. Mr Welles continuously wanted to indulge himself. He wanted the high life (for a time in his youth he was a playmate of children of Prince Aly Khan) and this is evident in his change from svelte young man to gross middle age.

In a previous review I wrote of my personal distress in relation to the collapse of the career of Erich von Stroheim. Here at least was someone who remained embittered to the very end because he was given no further chances. The loss to us as viewers is quite probably incalculable. Mr Welles was also a person of outrageous talent but at the end of the day, I don't think his desire to make films (I mean produce, edit and publish) was ever so strong. So to some extent the loss to us is less.

As to the film: it is certainly a must. I had originally thought that with 98 hours of shot footage, it would be well-nigh impossible to make a coherent whole of it, even with the reverential and extraordinary talents of those who subsequently put things together. I now think that it is highly likely that much of the footage was shot simply for the sake of shooting. I found the end product really quite moving and substantially coherent. There are some flat moments relating to inadequacies of the script and these have to be considered "errors". There are others which are deliberately so most particularly the footage of the film within a film. Once one is aware that this is Mr Welles as director casting aspersions on director Michelangelo Antonioni, the longeurs become more than tolerable.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.