In an earlier post which you can find here, serious cinephile David Hare wrote

about the silent films made by Julien Duvivier. David has now written a

companion piece devoted to the decade of Duvivier’s greatest artistic success,

the 30s. The effort is heroic and I have to note that readers from around the

world, greatly assisted in part by some tweeting, are hopefully enjoying the

scholarship on display. This remains a long term project and contributions,

reviews of individual films, anecdotes, reports or whatever are most welcome

16 FILMS BY DUVIVIER

FROM THE 30S

This is an attempt to give thumbnails of 16 Duviv’s complete

feature film output for the 1930s. Four films are missing; of these, La

Venus du College from 1932 no longer exists, Le Petit Roi exists in a single print at the Belgian Cinematheque and,

according to Norwegian French cinema expert Oystein Tvede, La Machine a Refaire la vie

from 1933 is merely a film history montage from 1924 that was re-released in a

sonorized version in 1933. There is also a Maurice Chevalier vehicle from 1934,

l’Homme

du Jour which I can’t access.

Here is the remainder, and I want to briefly mention a small

dedicated clique of film collectors and hard working enthusiasts, saints all who

literally uncovered, curated and slaved over video searches, forgotten TV broadcasts

and semi clandestine 16mm and Telecine screenings, video tech repair work and

subtitling, and effectively magically regenerated this crucial chapter of film history,

in the almost complete absence of “official” sources, through a particular

closed web community. Special thanks to Neil McGlone, and to “Kinsayder” who

may not wish to have his name published at this time given the insane

straitjacket of the French so called “Intellectual Property” regime which has

itself been the primary cause of so much suppression of Duvivier’s and Charles

Spaak’s work for the last forty years plus.

With the advent of the Eclipse box and the 4k restoration of La Belle Equipe by Pathe now in the

works one hopes this age of exclusion and copyright malfeasance is coming to an

end.

1931 and David Golder. For his first talkie Duviv pounced on the

newly published 1930 novel by Irene Nemirovsky which documents a wealthy Jewish

financier and paterfamilias who ruthlessly makes his money through brutality

and mendacity, in large part to service the whims of his vain and self absorbed

wife and daughter. At a key point in the film he turns his life around, in a

stunningly filmed sequence in which he tries to choke his wife to death with her

recently acquired pearls. He leaves this

life behind and takes to the high seas in a state of terminal despair. Nemirosvky’s novel was centrally addressing

what she perceived as a “problem” she identified as a French (and European)

social issue at the time; the so-called “Good Jew/Bad Jew” issue. Given the concerns

of anti-Semitism that arose over the following years , and despite her own

Jewishness, these tended to dog her

through her career up to her tragic deportation to the camps during the

Occupation and her murder by the Gestapo in 1942. Duviv’s wife was also Jewish and his cycle of

20s Catholic devotional films as a devout believer had come to an effective end

with the now highly ambivalent late 1929 silent La Divine Croisiere (the Divine Cruise) when it had become clear he

was losing his faith. Thus the volume of films with biblical and Christological

material that so marked his silent period would be reduced to only one striking

sound film in 1933, Golgotha.

Duvivier worked with Nemirovsky to minimize the Bad/Good Jew

dynamic of the book re- shaping the material textually to incorporates his own growing

misanthropy, a personal characteristic that would never be absent from his later

work. And thus it is for this first striking talkie, in a film similar in genre

to L’Herbier’s L’Argent (1929), David Golder is certainly the equal of if

not actually superior to L’Herbier’s film. It has a deft blending of European-wide social

spectacle with an intensely private emotional vision.

Of a small number of films inspired by the beautiful Pal

Fejos silent/part talkie romantic comedy Lonesome (1928),

my own favorite is Allo Berlin, Ici Paris (1932). This is Duviv’s first UFA co-prod

through Tobis Klangfilm with both French and some German dialogue. The film’s technical and social dimensions give

voice to the relatively new

transcontinental wire services and easy rail travel between France and Germany,

so the endless narrative opportunities for the lead boy’s and girl’s missed

meetings and all the tropes of that romantic sub-genre are deftly explored

through the screenplay. If there were ever a classroom for comic timing and

pacing this movie presents itself. The tone of this beguiling little film never

wavers from gentle, and the sentiment of

looking forward to a united Europe is both touching and melancholy given what

was about to happen in Germany. This is

essentially genre Duvivier and he’s clearly a master of it. Unmissable.

Les Cinq Gentlemen Maudits (Moon Over Morocco, 1933), also

unmissable, is a seemingly lightweight but surprisingly personal journey film

and the second in which Duviv travels to his beloved Algeria (the first was in

the Divine Croisiere in 1929.) The film is largely overlooked and little seen

(the source I have is ragged) but he delivers a pictureque personal diary-style

tale of a group of men (invariably) whose comradeship on the holiday is tested

and under threat from the appearance of “woman” into the pack. Here is another central

theme in many of Duvivier’s movies, the bonded male group and its undoing by a woman

which, in this comedy-drama, takes a bittersweet tone. It clearly suggests the

far more sinister later themes of betrayal and treachery that characterize his reputation

by some (if not me) as misogynist. The tone here is the thing to watch, pre-Charles

Spaak and his development with Spaak of the “meddling female” notion into the fully

blown Femme Fatale character a couple of years later. Harry Baur who first acted for Duviv as the

paterfamilias in David Golder is lead

here, along with the sublime Rene Lefevre, an archetypically sweet French actor

“type” whose shy masculine beauty is the defining feature of his unforgettable

roles here, and in Renoir’s La Crime de M.

Lange (1936) and Gremillon’s astonishing Gueule d’Amour (1937).

A German-language version of this was made with Anton (then

Adolf) Walbrook released through UFA. I have not been able find any source for

this.

And again in 1933

Duvivier revisited Poil de Carotte (Carrot

Top), now with Harry Baur. Along with the addition of panchromatic film stock

and long lenses Duvivier could now shoot great slabs of the film outdoors with greater

freedom than previously and the mise-en-scene

of this talkie version of the beloved weepie has both the benefit of superior

actors to the 1925 silent, and a much more limpid and fluent visual style. I

still think it’s a “project” picture as much as a personal project but he

infuses it with hints of threat and unease that aren’t necessarily a given from

the novel. Certainly in terms of novelistic adaptation it’s a demonstration

piece, as are all his fictional adaptations from this point on.

|

| Valery Inkijinoff in La Tete d'un Homme |

Maria Chapdelaine (1934) brings Jean Gabin to Duvivier’s world,

and both of them to Quebec French Canada. If this beautiful, great outdoors

romance and journey film reminds me of any film it’s Vidor and Northwest Passage (1940), but the three

man, three woman narrative here has inflections of conflict and unease that are

again Duvivier-esque. This is one of

three Duviv 30s pictures magnificently

restored and released on excellent French Warner DVDs back in the mid

2000’s.

Golgotha (1934) is the very last of Duviv’s “devotional”

cycle of pictures, albeit one made after he had essentially abandoned his

Catholic faith for non-belief. As one who is genetically allergic to Biblical

costume pictures myself, I find this unlike almost any other similar movie - an

unusual blending of action film with meditation. Gabin plays Pontius Pilate in

a fetching combination of flowing curtain fabric toga and page boy wig. Once

one gets over the costume aspects as one always must with these things, it’s

actually a compelling action narrative of guilt and responsibility. The cast

includes Baur, again and the first time

in Duviv’s canon Robert le Vigan,

playing Christ (!!), the notable young actor who would appear in key films from

Renoir and Carne up to 1939 and his role as the suicidal poet maudit in the

fabulous Quai des Brumes (1938). Le

Vigan sadly became better known as a rabid anti-semite and Vichy supporter

during the war.

La Bandera (1935) is Duviv’s first film with Spaak as

screenwriter and his first with Gabin playing the original “mec on the lam”

precursor to the eventual France/Algeria/otherness trope that formalized the

new era of Poetic Realist cinema. I love this movie to death. The apparently

outrageous narrative lurches from one continent to another, from chamber drama

to Foreign Legion battle epic with the introduction of the Fantastic “Other”/Woman,

in this case the actress Anabella in heavily applied Egyptian Dusk, whom Gabin

weds in a staggering blood sharing ceremony of outrageous eroticism, in one of the

high points of 30s French/Algerian exoticism. An early scene with Gabin on the

lam in a dive in Barcelona has him circled by and then embracing bare breasted

flamenco dancers and ruthlessly butch-faced drag queens just before he’s picked

off by his fellow Frenchmen who steal his passport and set him up for

deportation. While administering his usual dose of corrupt cynicism Duviv here

manages to depict decadence and sin with the most and endearing glee. There’s a

true spirit alive here folks. And another superb Warner France restoration from

2005. Le Vigan turns up later in the Legion along with a bevy of unlikely

characters including a short dumpy “American” actor who has befriended Gabin

and who seems to be gay, as he is constantly wrestling off le Vigan and sitting

on his face to keep him at bay. There are some unbelievable things going on in

this masterpiece by an unabashed man of the world .

|

| Viviane Romance,star of La Belle Equipe |

If there’s any such thing as a common accord about Duvivier

it’s probably that his next film La Belle Equipe (1936) is an undisputed masterpiece, and

possibly also Spaak’s I think. I don’t want to say much more prior to a major

4K restoration and Blu Ray release next year except that this is a peak

thirties French cinema, a peak Duvivier and peak Spaak. This is the very heart and

soul of Poetic Realism, all the more as the faith in the “Group” or the

“Collective” is so frail it ultimately collapses in tragedy. The film also seems

to predict the rise and the fall of the Daladier government and the turmoil

that will engulf France by the start of the War.

Duviv’s 1936 remake

of the frequently filmed Le Golem

again stars Harry Baur in a relatively energetic reworking of the oft –visited

subject. It’s his least interesting film from this period to me, but it

requires a re-viewing.

Duviv’s 1936 remake

of the frequently filmed Le Golem

again stars Harry Baur in a relatively energetic reworking of the oft –visited

subject. It’s his least interesting film from this period to me, but it

requires a re-viewing.

The next film is possibly one of the best known Classical French films of all time, Pepe le Moko (1937), another great Spaak screenplay set in Algeria with a flawless cast including the extraordinary Mireille Balin, the female lead who goes “slumming” in Algiers and becomes sexually enthralled with Gabin. There is already a mountain of commentary written on this wonderful movie but I would only add some recent notions that the playing by Mireille Balin, indeed Duvivier’s direction of her, is alchemical, as though while giving her the dimensions of a flesh and blood Femme Fatale, she seems to remain untouchable, almost ethereal, beyond judgment, simply without guile of malice, despite the nightmarish consequences her appearance has triggered. I adore the actress and her parts in this, Gremillon’s Guele d’Amour (Spaak again) and Delannoy’s very funny, and rich 1939 dawn of war adventure pic Macao L’Enfer du Jeu. She is a neglected and tragic figure in French cinema.

Un Carnet du Bal (1937) has happily had a more extended life in

repertory cinema and its reputation is deserved. Among other things it deploys

a large ensemble cast with finesse and Duviv can explore that variety with narrative

depth.

And it’s not far in

some respects from his first American film, made on a first “Scouting mission”

to Hollywood in 1938, The Great Waltz

for Metro. More than pure Duviv sadly

the movie strikes me as pure Louis B and it’s frankly a miracle the exercise

comes off with as much grace and style as it does. Duviv was not happy doing

the project, indeed while MGM under the hideous Mayer in particular could and

did smother any auteurist with ease, it must have been especially galling to

Duviv. Personally the single most beautiful and surprising things in it is the

post production addition of a gorgeous

Waltz montage filmed by Sternberg as “filler” to a totally ham and baloney finale directed by Victor Fleming after Duviv

had fled back to France.

Which leaves us with two more pictures in 1939:

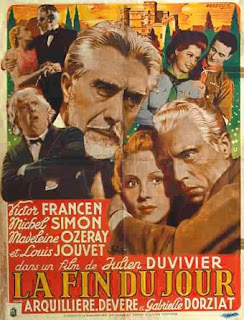

La Fin du Jour, written by Spaak (his final screenplay for

Duviv) is perhaps the director’s best ensemble piece. It is set in an actor’s

“retirement “ home with another gift

cast for the day, especially the sublime Louis Jouvet. For people who enjoy the greatness of so much cinema

by directors like Cukor and Carne, with their focus on performance and text,

this resides in the stratosphere alongside both those masters’ work. This is

the film I wish Sondheim had become attached to for a possible musical, rather

than La Fete a Henriette (1952).

Then a remake of the

Sjostrom silent picture La Charette Fantome

(The Burning Chariot)

(1939), an energetically stylish forecast of the horrors that many were feeling

about the oncoming war. It’s not intentionally an allegory for the imminent war

but it has great power as personal expression. Fantasy and delirium are never

very far away.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.