Set in 1859 and based on real-life events that followed the discovery of oil in rural Titusville, Pennsylvania, High, Wide and Handsome is a winning Paradise-lost musical written for the screen by Jerome Kern (music) and Oscar Hammerstein II (lyrics). Hammerstein and George O’Neil (Only Yesterday, Magnificent Obsession, Intermezzo) are officially responsible for the screenplay, although it underwent some major uncredited revisions by director Rouben Mamoulian.

|

| Rouben Mamoulian |

The film has been generally reduced to a footnote in histories of the musical, cast in the shadow of Mamoulian’s major work in the genre (Applause, Love Me Tonight, Summer Holiday, Silk Stockings) (1). That said, it hasn’t been entirely ignored: in a programme note for London’s National Film Theatre, Richard Roud enthuses about it as “an extraordinary fusion of Brecht and Broadway” (2); Clive Hirschhorn sees it as “one of the screen’s few really worthwhile musical Westerns” (3); Douglas McVay suggests that Mamoulian directs it “with far more style than he shows in Love Me Tonight” (4); Jeanine Basinger sees it as indicating that “Mamoulian is a major force in mixing the sense of realism available to movies into a musical format” (5); and, in his discussion of folk musicals in his excellent book on the genre, Rick Altman rates it very highly (6).

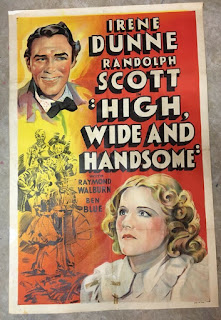

Randolph Scott and Irene Dunne take the leads, an unlikely couple, at least at first glance. They’d been an on-screen couple once before, in William A. Seiter’s Astaire-Rogers musical, Roberta (1935), although there they’d been the secondary love interest. Not exactly providing comic relief, but certainly serving as a contrast to the central couple’s graceful, meant-for-each-other togetherness.

|

| Irene Dunne, Randolph Scott |

Here, though, they’re the main act (with Dunne featuring above the title and Scott immediately below). He’d played the lead in a number of low-budget Zane Grey-adaptations earlier in the 1930s, but was still a few years away from the stardom that he acquired through a host of westerns. She was fresh from her role in Hammerstein’s Show Boat (another folk musical, which she’d also played on stage), and The Awful Truth (1937) was waiting in the wings.

Scott plays Pennsylvania farmer Peter Cortlandt, an upright small town citizen who falls in love with chanteuse Sally Watterson (Dunne), the “snippy” daughter of a travelling snake-oil salesman (Raymond Walburn). The adjective comes, approvingly, from Peter’s farm-workers. After events conspire to bring them together under the watchful eye of his endearingly feisty grandmother (Elizabeth Patterson), their wedding day coincides with the discovery of oil on the Cortlandt farm and their Eden is transformed into a much more modern environment. “Now you can have everything you want,” rejoices Peter.

As Sally’s gorgeous song, “The Folks Who Live on the Hill" (click for a glimpse on YouTube), gives way to the sounds of the well exploding and the idyllic, blossom-covered rural surrounds are drenched in the spouting oil, the romance of the film’s early scenes evolves into a very different kind of story. Innocence gives way to a harsh reality as Sally is effectively nudged into the background and Peter battles to prevent the rights of the local community from being usurped by the might of Eastern money. She eventually returns, but only when she implicitly agrees to play the game according to the rules the men around her have dictated.

|

| Scott, Dunne - The Folks Who Live on the Hill |

The conflict is the same as the one underpinning many westerns, as well as Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), pitting the “little man” against the forces that threaten to make him irrelevant. It’s essentially a case of Good Capitalism (the one that caters for all the people) colliding with Bad Capitalism (the one that has been commandeered by a greedy few). Walter Brennan (Alan Hale), the jovially cold-hearted railway boss plans to freeze the landowners out by forcing them to pay exorbitant rates to have their oil transported for refining. This is Bad Capitalism. “All it amounts to is plain, everyday stealing,” Peter protests when Brennan proposes a deal with him behind his neighbours’ backs: “A few men stealing from a lot o’ men.” Brennan tells him he’s right: “That happens to be a pretty good definition of business.”

With Mamoulian’s camera tracing a graceful arc around the communal rituals that define the world of Titusville, High, Wide and Handsome is a classic tale of a Garden of Eden being tainted by the Original Sin of Big Business. And, after the coming of oil, it’s clear that it’s going to be impossible to turn back the clock. But there are serpents in this Eden even before the derrick spews forth its black gold. Most prominent among them are the puritans led by Red Scanlon (Charles Bickford), hostile to those of a more liberal mindset (like Peter and his family), brutal in their treatment of outsiders, and hypocritical in their misogyny. It’s remarkable how often the seeds of discontent in American films (and in American life generally, both before and after the Civil War) grow within its own borders. And there’s no law officer in sight to keep the peace in Titusville.

|

| Dunne, Scott (with curls) |

|

| Akim Tamiroff |

While the vivacious Dunne is perfect for her role, Scott doesn’t seem altogether comfortable as Peter. At first, before the tensions explode, he’s at ease as the country boy: a hard-working farmer, a righteous gentleman defending a lady’s honour, appealingly comic in his awkwardness as a suitor. But when he’s required to plead his case and persuade the townspeople to stand with him, he’s less convincing. Scott’s strong, silent persona is that of a man who delivers the goods as a doer rather than a demagogue. But the actor seems ill-fitted to the demeanour of the character he’s playing, and the bizarre curling that afflicts his hair at various points in the film doesn’t help.

At this point in his career, Scott is still an actor in search of a place in the scheme of things: playing opposite or alongside stars, male (Grant, Astaire) or female (Dunne, Carole Lombard, Mae West), or juvenile (Shirley Temple). Sometimes he’s at home there (especially with Temple), but, viewed in retrospect, it appears that the qualities that were to make him a star, especially a star in westerns (from the Zane Grey adaptations through to his melancholic farewell, Guns in the Afternoon), are being repressed and, to a greater or lesser degree, he’s being forced into roles that don’t give him sufficient room to move.

1. see for example Jim Hillier and Douglas Pye’s 100 Film Musicals, pp. 132, 226

2. cited in Tom Milne, Mamoulian, p. 106

3. Douglas McVay, The Musical Film, p. 25

4. Clive Hirschhorn, The Hollywood Musical, p. 132

5. Jeanine Basinger, The Movie Musical, p. 70

6. Rick Altman, The American Film Musical, pp. 272 - 327

Editor's Note: An unrestored copy of High, Wide and Handsome is streaming free If you click here

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.