Hello Everyone

Just an early note to let you know that the full Cinema Reborn program will be released on 15 March. On that day you can drop in to the Ritz or Lido and pick up a copy of our splendid brochure listing all the films, session times and presenters. You will be able to log on to our website for all the information and links to bookings. We’ll be sending out another email closer to the date but if you would like to receive our brochure emailed to you as a downloadable Pdf document then you can order it in advance by emailing cinemareborn2025@gmail.com and just put “Receive Brochure” in the subject line.

In the meantime we have announced seven programs and you can read short notes and make a booking if you go to the Ritz Cinemas or the Lido Cinemas pages. On those pages you will find a link to purchase a 5 film ($80) or 10 film ($140) pass that will allow you to purchase a single ticket to any of our programs including our opening, closing and Saturday centrepiece sessions.

Charitable Donations

Cinema Reborn is grateful for the financial support of our donors. If your donation is received before 9 March you will be listed in the 2026 printed catalogue. Donations received after that date will be listed in 2027. Donations are used pay the screening fees to the archives and producers who supply our films and to keep our admission charges to regular Ritz and Lido prices (with the lowest student concessions of any similar film-related event).

We have once again set up a page via the Australian Cultural Fund to receive donations of any size, large or small. You can find it IF YOU CLICK ON THIS LINK

‘Katies’ — the new magazine publication of KinoTopia set to launch at ACMI

Fellow Cinema Reborn Organising Committee Member Digby Houghton has organised — with the help of KinoTopia — a screening of Eddie Martin’s 2005 documentary Jisoe at ACMI on March 24 to coincide with the publication of KinoTopia’s new print magazine Katies. More information and tickets available here.

KinoTopia is a weekly newsletter based in Melbourne and founded in 2023 as a means to promote underground and repertory screenings in the city and its surroundings. More information and how to subscribe can be found here.

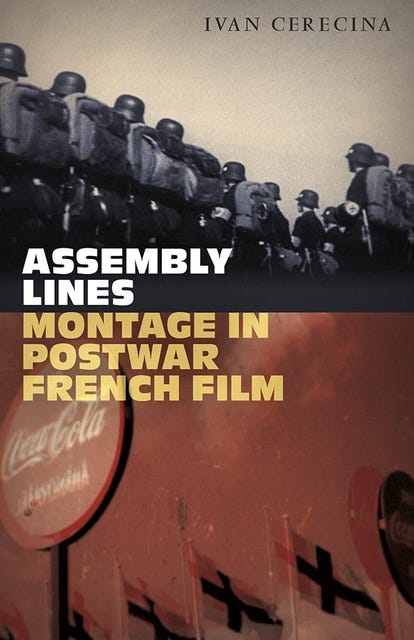

A New Book by Cinema Reborn Supporter and Presenter Ivan Cerecina

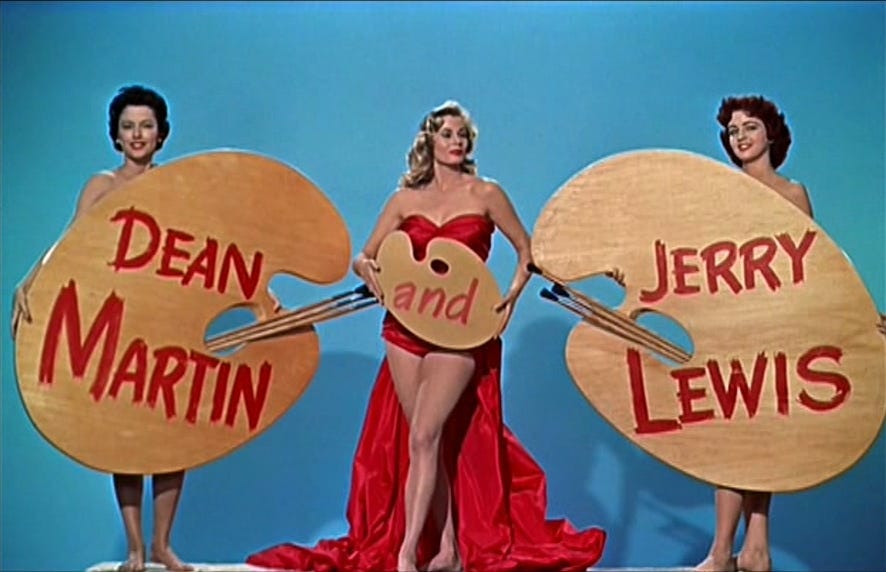

We are pleased to announce the publication of Assembly Lines: Montage in Postwar French Film, written by one of our Cinema Reborn presenters, Ivan Cerecina (The University of Sydney / Ivan’s website ). The book examines the re-emergence of montage as an aesthetic figure and historiographical principle post-1945, via a study of the early films of three important filmmakers of that postwar generation: Nicole Vedrès, Alain Resnais, and Chris Marker. It is published by the prestigious University of Minnesota Press.

The book is available for pre-order in Australia until the end of February for the reduced price of $40 AUD, via The Nile Bookstore

Readers outside of Australia on your list, but they can purchase the book via the University of Minnesota Press’s website

Red Matildas – A Restoration Project of a Major Australian Documentary

Trevor Graham writes: In the picture is some significant Australian film history: Mandy Walker (DOP now 48th President of the American Society of Cinematographers, DOP on Elvis, Return Home, Mulan, Snow White, Jane Got a Gun, amongst many others) and Laurie McInnes (Broken Highway, Palisades, On Guard amongst many others) shooting Red Matildas, in Fitzroy (Melbourne) 1984.

FRIENDS OF HISTORY, AUSTRALIAN CINEMA & DOCUMENTARY – WE NEED YOUR HELP.

RED MATILDAS returns to screens big and small in a stunning 4K digital restoration, forty years after its original 16mm national cinema release across Australia. This award-winning 1985 documentary, to be preserved for streaming, community and educational audiences, captures the spirit of three remarkable women who challenged inequality and militarism during one of the most turbulent periods in modern history.

Through the stories of May Pennefather, Joan Goodwin and Audrey Blake, Red Matildas explores Australia during the Great Depression: a time of mass unemployment, hunger, and the rise of fascism at home and abroad. It was a period that stirred many into political action, and these women placed themselves at the front lines of global struggles for peace and justice.

Red Matildas is more than a historical record. It is a powerful reminder of the enduring struggles for peace, justice and women’s rights, and of the courage it takes to stand against war, poverty and inequality. Resonating deeply with today’s world of social upheaval, economic hardship and conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, the film invites new generations to rediscover the passion and conviction of women who refused to remain silent.

Already 50% of the $25,000 needed to restore the film has been raised. Those interested in donating to support the restoration of this award winning and irreplaceable film can learn more here:

Tax Deductible Donations through Documentary Australia

We hope you can support the ongoing life of this significant Australian documentary.

We look forward to seeing you at Cinema Reborn 2026.