The series on the 60 years international of art cinema 1960-2020 by Bruce Hodsdon continues with summary notes in a supplement (unnumbered) on the background to the formation of the series and related issues (see below).

These notes are intended to accompany the summary table and decadal lists of art film directors 1970-2020 (click to link) which contain 5 lists 1970-2020 including a list of women art film directors over the full 60 years from 1960), The sixties is the subject of an on-going separate annotated listing of directors in part 6 divided by nation-states in multiple sections.

The notes in this instalment are on methods of selection, criteria for canons, national versus nation-state cinemas, second versus third cinema, and the question of “a new kind of cinema”?

The annotated list for the 1960s will continue with Part 6 (2) Hitchcock, Romero and art horror.

***********************

Moving into 'the main game', part 6, an annotated grouping, by country, of filmmakers placed in geopolitical groupings identified as active directors of art films during the 60s. These are designed to match the summary table (linked above) showing numerically the distribution of these directors covering six decades 1960-2020. A director appears once in the decade in which they first made some critical impact.

Method

The identification of filmmakers is made in global databases, primarily Wikipedia and IMDB, where entries of basic career information is the potential field from which more than 800 filmmakers have been listed.

In the selection of names with which to search the databases I have not followed any systematic process, it is an impressionistic mix of memory, retention of information, reviews and analysis available in print and online. It is also cumulative (one filmmaker identification tends to lead to another) over the course of a number of years, becoming a specific project c 2017.

As both discussed and implied throughout the survey, collected identification of the expressive presence of the director is at the core of the selection for listing. The sign of major change with the postwar rise of art cinema is the full crediting in the anglo-sphere of the director’s role also in the writing if applicable, in line with the general practice in European cinema where the director generally shares writing credit. This marked not just a change in the previously guild-imposed rules in Hollywood but also reflects the increasing proportion of emerging and established writer-directors following the end of the studio system and the rise of independent production .

With newly discovered filmmakers an impression is formed from available reviews (mostly online) and recognition of film festivals, giving provisional weight to recognition of formal and thematic innovation, identifying an emerging creative presence in international cinema. In general terms an oeuvre including theatrical release of at least three fictional or semi-fictional art features in narrative form is required for listing.

Canonical Criteria

What I’m attempting to do in this survey is to provisionally identify individual filmmakers from available evidence online and in print, as already indicated, from a loosely defined stream of filmmaking, chronologically and geographically located, but otherwise free of intra group hierachy. Implicit is that a canon of individual art films is contained in the sum total of their combined filmographies. While Galt & Schoonover in ‘Global Art Cinema’ are concerned mainly with setting parameters within which art cinema might best fulfil its role between mainstream and avant-garde cinema, Paul Schrader's focus in his ‘Film Comment’ essay in 2006 was on setting a framework in which judgement can be made, systematically applying nominated criteria in the placement of individual art films in the canon.

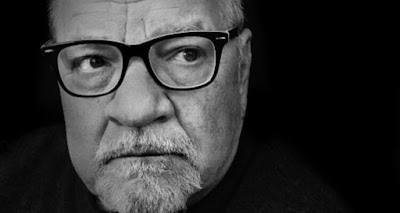

|

| Paul Schrader |

Polls most often base their appeal on the arguable premise that the relative quality of individual films can be determined by assembling the preferences from a constituency that is usually ill-defined or hardly defined at all. Some meaning can be restored by giving definition to the constituency ranging from a single individual to a defined group, eg the Sight & Sound’s decennial world poll grouping of voters into critics (including scholars and film programmers) and film directors. Since digitisation, the BFI has also made available online, in their groups, individually identified choices of ‘ten best films’ in addition to the votes of the combined constituencies. A canon of (art) film directors is then assembled from the voting for individual films. In the 2022 poll soon to be published it seems that a new (readers?) category of voters has been introduced. Schrader was commissioned by a publisher to write a film version of 'The Western Canon' (1994) which literary critic and teacher Harold Bloom applied to literature. Following the Bloom model Schrader determined that the selection of criteria should be elitist, not personal and popular, focused on art rather than mainstream films, based on criteria that transcend taste. Schrader soon realised that to draw up such a list required setting criteria for selection. This in turn required not only knowing about cinema history but also the history of canon formation in the other arts. This sent him back to school taking classes in the history of Aesthetics (“like the canon, a narrative”), of Art and by extension, on the history of Ideas, only to finally abandon the project (“my foray into futurism had diminished my appetite for archivalism”). He formulated seven criteria for judgment which are set out below in edited form.

It's much easier to make a list than to give reasons why...Standards of taste do not restrict art; the work of art will work around rules . They do, however, establish a necessary framework for judgement. Seven may be too many or too few.

Beauty is the bedrock of all judgements of taste...The solution to the problem of beauty is not to deny its powers but to expand its parameters...Beauty is not defined by rules and attributes but by its ability to transform reality...Seeking to free “beauty' from its cliché-ridden contemporary usage, is to relocate it in disparate cultures (Sartwell).

Strangeness is the type of originality that we can “never altogether assimilate” (Bloom).The concept of strangeness enriches the traditional notion of originality, adding connotations of unpredictability, unknowability, and magic...Originality is a prerequisite for the canon- it is the addition of strangeness to originality that gives these works their enduring status. Strangeness is the Romantic's term and Hegel's and everyone else's thereafter – until supplanted by the more recent “defamiliarization.”

Unity of form and subject matter. It's hard to argue with this traditional yardstick of artistic value. “The greatness and excellence of art,” Hegel states in Aesthetics, will depend upon the degree of intimacy with which... form and subject matter are fused and united.” Mechanically reproduced art greatly – and deliciously - complicates the possibilities of this unity. Motion pictures are multiform, juxtaposing real and artificial imagery, music, sound, décor, and acting styles to contrasting effect. Film does not have a “significant form.,” it has significant juxtapositions of form...In a “great” film the frictions of form join to express the interplay of functions in a new “strange” way. It's impossible to discuss the form of Rules of the Game without also describing its subject matter.

Tradition. T.S.Eliot argued that “no poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists.” Bloom picks up the argument in The Western Canon. Tradition is not only handing down the process of benign transmission,” he writes,”it is also the conflict between past genius and present aspiration in which the prize is literary survival or canonical inclusion.” This argument is particularly applicable to the fast moving history of cinema. In a hundred years the movies have redefined themselves a dozen times...One of the pleasures of film studies is stacking those filmmakers atop each other, seeing them reprocess their predecessors and fellow directors...The brief span of film history makes the task described by Eliot and Bloom more immediate. The greatness of a film or filmmaker must be judged not only on its own terms but by its place in the evolution of film.

Repeatability. Timelessnes is the sine qua non of the canonical...Films were not originally designed to “hold up.”...The ability of certain films to retain their impact after repeat viewings is a textbook example of what makes a “classic.”

Viewer Engagement. A film specific criterion that derives not from history but from the passivity of the filmgoing experience...A primary appeal of the movies may be in fact that they ask so little of us...A great film is one that to some degree frees the viewer from this passive stupor and engages him or her in a creative process of viewing. The dynamic must be two-way.The great film not only comes at the viewer, it draws the viewer toward it... A great film, a film that endures, demands the viewer's creative complicity.

Morality. Schrader admits his reluctance to introduce the oldest (and hoariest) artistic creation stretching from Plato through Kant to Ruskin and Leavis. He admits Triumph of the Will to the argument (or it could be 'Birth of a Nation?) as a work of moral resonance good or bad. Most agree that [ Riefenstahl's film] is evil. That's beside the point Schrader insists. It is arguably the quintessential motion picture, the fulcrum of the century of cinema, combining film's ability to document with its propensity for narrative... The point is that no work that fails to strike moral chords can be canonical.

Filmmakers in the canon fall into at least three categories: those whose body of work has already attracted sufficient consensus, those gaining or losing ground in the process of doing so, and those that have recently attracted attention.

I have further summarised the above seven criteria in their order as a framework for judgment of a director’s films :

- Beauty measured by its ability to transform reality

- When originality cannot be fully assimilated by the viewer

- The degree of intimacy with which form and subject matter are fused and united

- The film’s place in the evolution of cinema

- When the film’s impact on the viewer is retained over repeated viewings

- When the viewer’s creative complicity is demanded

- No work that fails to strike moral chords can be canonical

I have not attempted, in the listings, to set up a ranking of directors’ oeuvres in order of relative ‘greatness’ globally or even in their decadal nation-state groupings. Schrader’s criteria are put forward here to suggest a possible framework for canon formation - “seven [criteria] may be too many or too few” - of individual oeuvres that are immediately applicable as benchmarks established by the expressive formal and thematic originality of the narratives making up the body of work, for example, of Bresson, Ozu, Dreyer, Tati, and Straub-Huillet.

Schrader, a practicing filmmaker writing in 2006, is certain that cultural and technological forces are at work that will change the concept of “movies” as we have known them... The century of cinema is but a transitional phase, a canon should acknowledge that fact by (1) evaluating movies in the context of a transitional moment; and (2) by embracing a multiplicity of aesthetic criteria.

The above canonical framework is condensed from Schrader’s ‘Preface’. In an appendix he sets out his own 60 film canon drawn from what he sees to be the ‘transitional’ century of cinema.

National versus nation-state cinemas

I need to acknowledge here the limitations of my system of classification based as it is on linking the notions of the author and the national in seeking to provide a brief chronicle and review of postwar cinema’s globalisation gathering momentum in the 60s of which the statistical table of my selections provides some indication of its spread over time. These are issues that the IFG with the piecemeal annual contributions to its world production survey from a range of nationally based correspondents sought to document. Due recognition has been given by the editors of ‘Global Art Cinema’, for this pioneering work quoted in my introduction and in a summary essay on the scope of the International Film Guides’s 48 annual issues 1964-2012 linked to the AFI-RMIT Research Library and available online. There is some irony in the fact that the IFG appeared to be entering a new phase when the founding editor Peter Cowie retired in 2003 to be replaced by Daniel Rosenthal (2004-6), and after a year’s break, by Hayden Smith (2008-12). In fact as previously mentioned it was struggling with the loss to the internet of advertising revenue.

In the 60s, noted above as a watershed decade, postwar decolonisation was applying increasing pressure on the decolonised nation’s retention of its previous imposed political unity, culture, and economy. In the decades from the 70s onwards the speed, scale and volume in the free global movement of people, finance, technology, and electronic media images arising in this fluid environment transformed the concept of the post-national in a multipolar world. Stephen Crofts in his essay ‘Concepts of National Cinema’ (1998) notes the implications of these shifting hierarchies of power for the study of national cinemas. Such disjunctive relationships are most epitomised by the breakup of the former Yugoslavia, with its “five nations, three religions, four languages, and two alphabets… standing as a grim emblem of the role of the state in suppressing cultural differences.” As a result Crofts chooses “to write of state and nation-state cinemas rather than nations and national cinemas while clearly differentiating states within a federal system,” and without collapsing all into totalitarian states (386) .

Second versus Third Cinema

In this geopolitical landscape subject to the growing forces of globalisation, the role of the state was most often directed to subsidising production but not distribution or exhibition within the nation-state ( as was the case in the Australian film revival) which internationally shifted to the state importing the film. The space for anti-state cinemas in Latin America for example was very limited emerging from the underground in the case of the onscreen polemic for a Third Cinema initially in Argentina or the cross subsidisation of art films by the Fifth Generation filmmakers that was possible in China in the 80s, pre -Tiananmen. Art films offer the most consistent prospects for international exposure for a national cinema initially through film festivals while being subjected in this exhibition to the vagaries of cross-cultural readings. A successful mainstream film in the home market becomes an art film (with sub titles) in the importing country.

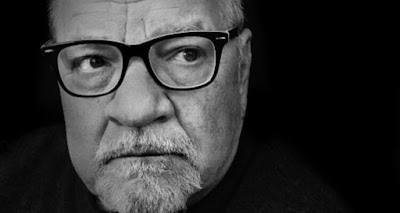

|

| Fernando Solanas |

Inspired by the Cuban Revolution (1959) and Brazil’s Cinema Novo, the notion of the Third Cinema was first put forward as a rallying cry both onscreen in La Hora de los Hornos (1968), and in a subsequent manifesto. Third Cinema was conceived by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino as a ‘guerilla’ cinema oppositional to the First (mainstream ‘Hollywood’) and Second (‘European’ auteurist) Cinemas, transforming the mode of production from industrial to artisanal, and reception from a passive socially fragmented audience to an often clandestine but participatory community-based one involving mobile projection units and locally led discussion.

Third Cinema filmmakers are listed in this survey as outliers within the Second Cinema umbrella on historiographic grounds. The New Latin American Cinema was in fact closely linked with the European new waves sharing stylistic similarities and travelling the same festival paths while being adopted by a number of European film critics. Third Cinema inspired filmmaker and theorist Bolivian Jorge Sanjines was led to remark that the NLAC was better known in Europe than in Latin America. Hanlon notes that Sanjines, despite his dismissive critiques of art cinema and his commitment to making films “with the people,” the dialogue between Second and Third cinemas in his critiques and films was central to his project of creating a new cinematic language (Hanlon 352). Burton-Carvajal further comments that in the 80s, with new generations less ideologically inclined “and the recognition that marginal and mainstream, dominant and oppositional film cultures are inextricably mixed, the impetus for manifestos declined (589).”

|

| Satyajit Ray |

A new kind of cinema?

In the early sixties there was definite sense that a new kind of cinema was developing, though there was little agreement on what its specific characteristics actually were. For myself as a 20 year old emerging cinephile, although I had yet to master the appropriate terminology, there was ‘de-dramatisation’ (L’Avventura), a more ‘direct approach to reality’ in fictional narrative (Umberto D, The World of Apu), ‘reflexivity’ (The Testament of Orpheus) ‘psychological’ time-driven plot (Hiroshima mon amour) and a rapidly increasing sense of censorship-driven denial (Breathless, The Virgin Spring). Above all, the director’s name began appearing with increasing frequency before the title indicating singular expressive agency when the film was spoken or written about. So the question became: “Have you seen the latest Bergman?” Within a year or two this form of identity-based criticism, initiated by a small minority of Paris and New York based critics, was being applied to genre films produced by the studio system in Hollywood:

It was relatively easy to locate art cinema as ‘not being Hollywood’: engagement of the look in terms of individual point of view rather than institutionalised spectacle, suppression of action, a tight causal chain being replaced by an episodic structure, more nuanced characterisation. Art cinema could be more ambiguous, reflexive and stylised and at the same time more naturalistic. Lacking strict parameters and with an ambiguous critical history it could be “identified for its impurity without losing its place as an alternative cinema between the mainstream and the avant-garde… Such difficulty of categorisation can be as productive to film culture as it is difficult for taxonomy” (G&S).

Art cinema began to be discussed as a concept in anglophone circles in the late 70s. David Bordwell classified five forms of film narrative, three being classical (the ‘invisible’ Hollywood style), historical materialist (Soviet montage) and art cinema with the innovations of Italian neo-realism extending through various European new waves. The latter culminated in a range of variations in film modernism reaching a peak across 13 European countries in the sixties to mid-seventies. Andras Kovács describes this modernism as inspired by the art-historical context of the two avant-garde periods in the 20s and 60s, art cinema becoming a cinematic practice different from commercial entertainment as well as from the cinematic [non-narrative] avant-garde.

|

| Saturday Night Fever |

Classical narrational mode was not subsumed by art cinema, it continues to co-exist with it. Bordwell notes that art cinema became a coherent mode partly by defining itself as a deviation from classical mode. When the narrative is tightly driven by causality (cause and effect) classical narration is dominant. Narrative coherence and patterning is a measure of classicism in a hybrid mix. When prepossessing visuals, bold use of music and the dominance of a single driving idea (‘high concept’ ) with plot and psychology secondary, as typified by Saturday Night Fever (1976) American Gigolo (1980) and Flashdance (1983), for example, classicism can assume a postclassical mode (Bordwell Hollywood Tells 5).

In the late 70s and early 80s Kovács notes there was a weakening in modern art cinema coinciding with the decline in cinema attendances in the face of great inroads made by videotape into home audio-visual entertainment, preceding the further seismic transformation of image production, distribution and exhibition progressively erasing the distinction between film and electronic technologies.

To extend the breadth of its spectrum of inclusion to acknowledge, in art film terms, directors of a select few mainstream blockbuster genre pictures such as Black Panther (2018) as outliers at one end, and Latin American political Third Cinema at the other, is to acknowledge G&S’s recognition of art cinema’s “elastically hybrid character” to explore central questions for current media scholarship. They further claim art cinema as “a critical category best placed to engage pressing contemporary questions of globalisation, world culture, and how the economics of transnational flows might intersect with trajectories of film form” (3).

*****************

Geoffrey Nowell-Smith “Art Cinema” Oxford History of World Cinema 1996

Steve Neale “Art Cinema as Institution” Screen v.22/1 1981

Paul Schrader “ Preface The Book I didn't Write Film Comment September-October 2006

Rosalind Galt & Karl Schoonover “Introduction” The Impurity of Art Cinema Global Art Cinema 2010

Stephen Crofts “Concepts of National Cinema” The Oxford Guide to Film studies Hill & Gibson eds.

Murray Smith “Modernism and the avant gardes” Oxford Guide ibid David Andrews “Towards an Inclusive, Exclusive Approach to Art Cinema” Global Art Cinema.

Dennis Hanlon “Jorge Sanjines, New Latin American Cinema, and European Art Film” Global Art Cinema op cit pp 351-65.

Julianne Burton-Caravajal “South American Cinema” The Oxford Guide ibid

David Bordwell Narration in the Fiction Film 1985; The Way Hollywood Tells It 2006

**************************

Previous entries in this series can be found at the following links

Part One - Introduction

Part Two - Defining Art Cinema

Part Three - From Classicism to Modernism

Part Four - Authorship and Narrative

Part Five - International Film Guide Directors of the Year, The Sight and Sound World Poll, Art-Horror

Part Six (1) - The Sixties, the United States and Orson Welles