I've had De Toth on my radar for many years. I put together the brief set of notes below a few years ago and should expand them into a more detailed account because I love this man's work: Important Hungarian/American director who made some significant Film Noir contributions and an impressive body of bleak Westerns many with Randolph Scott . Sarris includes De Toth among his “expressive esoterica” and fittingly describes his “most interesting films (revealing) an understanding of the instability and outright treachery of human relationships”. He is a master of tight, cramped action sequences in confined spaces.

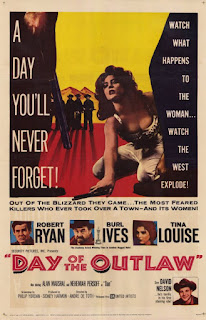

DAY OF THE OUTLAW

Day of the Outlaw is an austere black and white western set in a small community in the bleakest of snow scapes where Burl Ives as a vicious outlaw on the run takes over until he is finally challenged by rancher Robert Ryan.. De Toth’s direction is as cold as the ubiquitous snow. Ryan, as usual, delivers a magnificent performance of contained steel; Burl Ives’s part is showier but no less well-judged. Their final shootout in a blizzard unleashes De Toth’s claustrophic mise-en-scene at its most extreme. Along with the ridiculously neglected Ramrod, this is De Toth’s greatest contribution to the western.

RAMROD

One of the most bitter of all range war westerns, Ramrod is an early example of Andre De Toth's muscular intensity that characterises all his work in the genre through the string of very satisfying Randolph Scotts in the 50s to the extremely bleak Day of the Outlaw (1959). Joel McCrea is just fine as the initially weak cowpoke who tries to keep peace on the range in the face of two rival camps, one led by rancher's daughter Veronica Lake (in a ferocious, chilling performance) and the other by tough hombre Preston Foster, who loves and is rejected by her.

De Toth handles the complex plot and screenplay with his usual sharp explorations of shifting allegiances and betrayals of trust; Don Defore's edgy performance as McCrea's erstwhile friend is pivotal in embodying the film's dark mood and tone which some commentators have labelled noir.

PITFALL

Pitfall is a low-key work about a very suburban, very married insurance claims man (Dick Powell) who is drawn into a dangerous relationship with noir icon Lizabeth Scott (in one of her most nuanced performances). Raymond Burr is around as a private eye equally infatuated with Scott. Jane Wyatt is the wife attempting to reclaim her husband from Scott's clutches. Like all of De Toth's better films, it’s about betrayal and shifting allegiances-its low key virtues are impressive.

Sunday, 29 November 2015

Saturday, 28 November 2015

The Current Cinema - serious young cinephile Shaun Heenan reviews The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2

|

| Jennifer Lawrence |

The

Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 is the definition

of a critic-proof film. It’s the second half of the final movie in a series

with a built-in audience carried over from the popular novels. It gets the same

box-office whether or not it’s any good, because fans who are three movies deep

are going to watch it no matter what, and there’s no reason for anybody else to

jump in right at the end of the story. Despite this, those already invested

will find themselves in good hands here, as Mockingjay

Part 2 is the best in a series which has improved upon itself with each

instalment.

The film opens shortly after Part 1’s cliffhanger ending, finding

heroine Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) in hospital following an attack by

mind-controlled love interest Peeta Mellark (Josh Hutcherson). Stoic soldier

Gale Hawthorne (Liam Hemsworth) is the other side of the mandatory love

triangle, which has always been one of the series’ least interesting elements. From

here, the plot moves quickly towards an assault on the highly-defended Capitol,

with the specifically-stated goal of killing Panem’s cruel ruler President Snow

(Donald Sutherland).

Katniss has been chosen as a symbol of the

revolution – a capably violent but genuinely compassionate mascot – and much is

made of her involvement in propaganda. Even her final mission begins as a PR

exercise, as a film crew joins her on a fictionalised warzone expedition, well

behind the front lines. Alongside this examination of wartime machinations, the

film also offers a number of creative action setpieces, as the team activates

various traps strewn about the city. The best of these is a well-crafted horror

sequence set in the city’s sewers, where the group is relentlessly attacked by

eyeless creatures. Don’t take your kids to see this.

Now that it’s complete, it’s safe to say The Hunger Games is the best of the

recent spate of post-Harry Potter YA

novel adaptations. They’re all more or less the same movie (oppressive

government, armed revolution) but this franchise has succeeded through fine

casting. There are a lot of real actors in here giving real performances. The

head of the rebels is played by Julianne Moore, her opposite number is the

aforementioned Donald Sutherland and even young lead Jennifer Lawrence is an

Oscar winner. On a sadder note, this film will be the final screen appearance

of the late Philip Seymour Hoffman, who still had four roles ready for release

when he died in 2014. He was one of the great actors of his generation, and he

brings quiet confidence to his role here as a manipulative advisor.

Mockingjay

Part 2 is a strong ending to a relatively strong

series, but you already know if you’re likely to see it. It’s fair to take

umbrage at the increasingly-common trend of franchise films being split in half

to double the box-office take (Harry

Potter, Twilight, arguably The Hobbit), but in this case both halves make a

strong impression as standalone films. Nevertheless, it would be nice if that

never happened again.

A Cinephile's Diary (1) - Peter Hourigan reports on his week - the first of a continuing series

SUNDAY: –

I had just watched two items from Werner

Herzog’s filmography, when the invitation came to keep a Cinephile’s diary for

a week. So I should start with Lemonade Wars and Paper Bag. I was exploring them on YouTube because my film

discussion class this week will be talking about 99 Homes from Rahmin Bahrani, and I was checking him out on

line. These two shorts show him wearing

his social commitment openly on his sleeve, and it’s interesting that his

circle includes Herzog who appears in both.

Lemonade Wars is a perfect

companion for the feature, didactic, but then it looks like it’s been made to

make kids aware of how capitalism works to exploit and defeat the rest of us.

|

| Ramin Bahrani |

Looking ahead

at the week, there aren’t any specific cinephilic highlights planned, so it’ll

be interesting to see where the

inspirations that decide my viewing come from. Sunday night, I watch two films at home. The

back story for the first started when I came across one of those lists

populating the net at

vulture.com.

These lists

have become so ubiquitous that they’re often very questionable – and this one

is no exception. (Is Mother India really a musical?) But I’ve watched several things in the last

few weeks because of this last, including Om

Shanti Om (Farah Khan) about which I

was a bit dubious at first, because I’m not really into Bollywood

musicals. But I have to confess I loved

it – exuberant, quite moving, imaginative numbers, fabulous over-the-top

colour. So, I confessed this joy to our

resident Bollywood expert, Adrienne McKibbins, who drew something else to my

attention – Peter Bogdanovich’s At Long

Last Love, and an interesting

article about it on

indiewire.

So, there’s now this version that is not a director’s cut, but the musical fan’s cut that the director thinks is better than his. And it’s on YouTube. So, I had to watch this. I was surprised how few of the songs I knew, though I thought I had a good knowledge of the Cole Porter song book. The stars are clearly not professional

musical performers – but they’re enjoying themselves, and taking themselves seriously in an attractive “Let’s put on a show” way. Certainly not a dud, but in this cut very watchable.

I’m not sure where my next item of viewing came from, but I must have read some reference that induced me to buy The Unspeakable Act (2012) by Dan Sallitt. But whatever that spur was, I’m

glad of it. It’s an American Indie, about a young 17 year old girl, with a bit more than a crush on her older brother who’s about to

go away to College. There aren’t many films that immediately

come to mind about brother-sister relationships. Of course, two of the best are the hot-house films by Visconti and Cocteau, Sandra and Les Enfants Terribles. But this is more interested in how one sibling has to re-define the relationship as they pass from

adolescence into young childhood. Its style is uncharacteristic

for an American film – so restrained it almost disappears back into itself. But this suits the film,

which has a refreshing but quiet directness (which Adrian Martin comments on in his liner essay.)

This theme matches one of the themes in Eugene Green’s La Sapienza, where two siblings need to readjust their relationship at this point of their maturity. But this comparison also points up the

greater richness in La Sapienza[i]. This has several other themes playing through the film as well, all of complexity and imagination, and all four major characters are presented in depth. Any could

become the focus of the film. In Unspeakable Act, it’s really only the sister who we really get to

know. However, one of those films that makes you feel excited that there are still these new

discoveries to be made.

MONDAY -

out to a real cinema to see 99 Homes again, to prepare for my

class later in the week. I’m glad to see Rahmin Bahrani at last

getting some cinema screen time here – after all this is his fifth

film, and all the preceding works have been more than just

satisfying. In fact, I used his first film, Man Push Cart (2005) for several years as a teaching film for senior secondary media

students. In this new film his political and social awareness is

very much to the front, but it’s much more than just a political

piece of preaching because he takes us so strongly into his three main characters.

And tonight, perhaps made curious by A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Contemplating Existence appearing at ACMI I checked out Roy Andersson’s first film, A Swedish Love Story from 1970. A much more straightforward film, but it has a charm. He’s already

handling a broad cast, looking them over with his distinctive,

somewhat off-centre visuals and observations.

I’ve also “cleared” several films I’d recorded off SBS. A few weeks’ back I read Christos Tsiolkas’ review of The Lobster in The Saturday Paper and thought it was one of the best reviews I’ve read for a long time. This pointed me today towards Dead Europe directed by Tony Kravitz from a Tsiolkas book I haven’t read. It’s an interesting and ambitious film. Its scope is vast geographically and thematically. But the film is weakened by some inadequate performances in a few of the small, but still important minor roles, which have the effect of leadenly pointing up these themes. Meanwhile all I’ll say about Stuart Gordon’s Reanimator is it’s really not my type of film. It has the exuberance and pace of full confidence in its pulpy story, but I’m not its demographic.

TUESDAY. Other things in my life – a class I’m doing on Ancient Egypt late morning, and the end of year get together of my book group. But in between of course a Cinephile fits in a film. If I saw the original Argentine film I don’t remember it. Billy Ray’s remake The Secret in Their Eyes is certainly diverting, but ultimately disappointing. Some years back I used his Shattered Glass with secondary students, and I like the way it tackles important issues. It’s one of the best films I know on journalistic ethics. But this new films flubs it on ethics, and its resolution falls back into the good old American Vengeance format, and ethics, law and society are all finally less important than one person avenging herself.

WEDNESDAY Cinematheque for my cinephile addiction today, and the final night of the Miklos Jancso set. Tonight The Red and The White and My Way Home. Seeing six in fifteen days is probably some form of masochism. I respect his incredible power with his choreographed actors, horses and camera over the vast Hungarian plains. But I rather feel I’m doing a penance watching them, rather than really getting caught up and involved.

THURSDAY The focus for my day, was my evening discussion class on 99 Homes. During the day, I prepared by picking up a few extracts from Bahrani’s earlier films, and it was a pleasurable indulgence to revisit them – especially his first Man Push Cart. I also looked again at several of the shorts

on YouTube, which is where I started this week. Lift You Up made for a project sponsored by Mont

Blanc pens, is from his very empathetic side, where in about 8 mins he builds a beautiful portrait of

an elderly man with such a wonderful outlook on life. The class itself went well. Everyone loved 99 Homes. I was interested that several of the members, when they commented on the performers

commented first on Andrew Garfield. In a lot of the write-ups first mention often goes to Michael

Shannon. His is a powerful performance, often dominating the screen as his character dominates his part of the world. But Garfield’s performance is surely even more wonderful, cutting right into the

being of this man who under pressure from the system makes that deal with the devil.

After the class I had time to look at a disc that arrived yesterday. Often new releases sit on my shelf

for weeks, but this I had to see straight away. I’ve never forgotten the impact of a rock opera I saw in London back in 1970, Catch My Soul created by a music producer, Jack Good. Billed as the ‘rock

Othello’, it moved the story from a garrison in Cyprus to an army fort in Texas. It was a transition that worked brilliantly, with the stage set of the fort resembling the original Globe Theatre, and the racial tensions of the story resonating strongly. When I saw the news of this new BluRay release, I was

surprised because I never even knew it had been filmed, back in 1973.

But not really a viewing experience that recreated that first wonderful memory. Some surprises in the credits. The film was directed by Patrick McGoohan, the only film he directed. And Conrad Hall was cinematographer. These aspects of the film are really good. But it seems that between the London production and the film, Jack Good “got Catholicism” and the whole focus of the story changed. The film takes place in a commune near Sante Fe, with Othello becoming the priest and Iago the Devil, and religious iconography abounding. It’s not a happy transmutation, losing the focus of the

Shakespeare original and not replacing it by anything really of much worth. The score is still

effective – Richie Havens is the Othello character, the photography is great, and it looks like all the

cast who took part in the desert party had a great time. I’m sure they were stoned all the time!

FRIDAY Not much time to indulge my Cinephilia today, but I did watch the recent Masters of

Cinema release of Oshima’s Cruel Story of Youth. It’s a well packaged disc, and Tony Rayns’ hour

long talk on the film is packed with information and insight.

In the Intray of the emails, was the results of Sight & Sound’s Top Ten for 2015, a warning that over the next few months we’ll be inundated with everyone one and their dogs coming up with their

lists. S & S’s lists are interesting because they’re upfront about how it is compiled and it is backed up with several hundred individual lists to become lost in. I haven’t had time to really start taking them all in, but a first reaction – there are certainly a lot of “brave” choices in the S & S list that I’m not

expecting to see appear in the nominations for Oscar! Not far behind came the Cahiers list – several overlapping titles.

SATURDAY.

Kon Ichikawa Today to a combined House Warming/80th Birthday.There weren’t any filmies there – but most had

seen The Dressmaker! Some, twice. Oh, well, they liked

it! And 80th birthdays don’t go late, so I was able to get to a 9pm screening as part of the Japanese Film Festival here of Kon Ichikawa’s Conflagration. It’s a long time since I saw this, but it’s still a great film. How wonderful, too, to

see it in a beautiful 35mm print, filling the huge ACMI

screen. ‘Scope is always wonderful on this screen.

And that was my week in film.

[i] A week later an interesting point. I made the link between this film and La Sapienza.

And now I’ve noted that Adrian Martin wrote the essay for The Unspeakable Act, and put La Sapienza in his Top Ten for 2015.

Friday, 27 November 2015

The Duvivier Dossier (37) - Max Berghouse reviews The Impostor

The Impostor (aka Strange Confession). Producer & Director Julien

Duvivier, Script, Marc Connelly and Julien Duvivier, Music, Dimitri Tiomkin

Cast: Jean Gabin (Clement/Maurice Lefarge),

Richard Whorf (Lt Varenne), Alan Joslyn (Bouteau), Ellen Drew (Yvonne), Eddie

Quillan (Cochery) and Peter (van) Eyck (Hafner). Universal Pictures, USA, 1944, 92 minutes

This American-made studio production is generally credited as terminating the Hollywood careers of both star and director. This seems worthy of comment. Jean Gabin was just one of many many European actors "stranded" in Hollywood, the bulk of them central European Jews. Most of these actors were fairly proficient in English whereas Gabin was not. And certainly not on the evidence of this film, where his limited grasp of formal language and idiom, accentuates a relatively wooden performance. His English certainly improved in the post-war period but it seems generally acknowledged that his career was set back by about a decade. Both he and the director very much wanted Hollywood success (who wouldn't?). Equally, while being by no means unattractive, he was not handsome in the general Hollywood mould and to some extent his lack of Hollywood success matches that of a similar actor: Maurice Chevalier, a decade before. By contrast and by way of example, Charles Boyer conveyed the smoothness of the boulevardier which American audiences would expect of a French actor.

This American-made studio production is generally credited as terminating the Hollywood careers of both star and director. This seems worthy of comment. Jean Gabin was just one of many many European actors "stranded" in Hollywood, the bulk of them central European Jews. Most of these actors were fairly proficient in English whereas Gabin was not. And certainly not on the evidence of this film, where his limited grasp of formal language and idiom, accentuates a relatively wooden performance. His English certainly improved in the post-war period but it seems generally acknowledged that his career was set back by about a decade. Both he and the director very much wanted Hollywood success (who wouldn't?). Equally, while being by no means unattractive, he was not handsome in the general Hollywood mould and to some extent his lack of Hollywood success matches that of a similar actor: Maurice Chevalier, a decade before. By contrast and by way of example, Charles Boyer conveyed the smoothness of the boulevardier which American audiences would expect of a French actor.

Lastly from the studio's

perspective (although this is purely conjecture on my part), by 1944, with the

war being clearly won, and with the gradual and then increasing return of

better-known actors returning from war service, they would have been little

need for such a problematical quality as Gabin. Similarly the film is generally credited as destroying any hope of a future

that Duvivier had of a continuing Hollywood career but I shall deal with this

issue below.

The plot is almost exactly the same as Raoul Walsh's Uncertain Glory (USA,1944). Both concern errant men seeking redemption by service in war to their country. Clement (Gabin) escapes from death row and almost immediate execution by the guillotine when his prison is bombed by the Germans at the very beginning of World War II. He escapes along with many other stranded French soldiers (played presumably by American actors who were considered unfit for military service) to the French Congo at Brazzaville where they construct a new camp in the jungle as a prelude to action against the Germans who were incidentally about 2000 miles away in Libya.

Setting the action in the colonial jungle

provides the opportunity of displaying a more or less imaginary colonial

landscape of sun helmets, very long shorts with long socks and some assorted

docile black people. It is very hard to take this seriously but it is no worse

and no better than many other films of the period. After all what did the

average viewer in Boise Idaho know about the French colonies? It is a mixture

of studio sets, footage of American woodland, presumably photographed as stock

footage in the Californian mountains, some stock footage of genuine jungle and

imaginary jungle. All quite typical.

Clement distinguishes himself in service, rising in the ranks to officer level and thus looking very distinguished wearing a Sam Browne belt. Not only is this "interlude" excessively long, it destroys any chance of real connection between the incipient plot of Clement as murderer (even one revealed as having had no real chance at life – of course there has to be some excuse for his crime!) and the denouement of his ultimate exposure and punishment. At the beginning Clement is a man without interest in life and this might be considered reasonable in view of his unhappy upbringing, even if this is simply described by him rather than experienced by us. Whereas Clement derives real purpose and apparent fulfillment in action with his buddies and for "the cause". Yet at the climax of the film, he sacrifices himself in circumstances that may not have been necessary and seem contrary to the enlightenment he has received in service to date. These are infelicities in plot and script which I think would have been corrected were not the director his own producer and scriptwriter.

A major inducement for the director to seek employment in Hollywood was to gain access to the studio system and its infinitely greater resources than those of his home country, France. Within the standards of the time, this is fully shown in the film I saw: the print is exemplary and crisp with clearly delineated gradations of light and shadow. There is only one battle scene, at the climax and perhaps for a film which would have been perceived as a "war film", the general lack of action would have told against audience reaction. That said this climax is exemplary, as least as so far as it concerns the French forces who seemed to be, at least partly in real-life surroundings (whereas their German counterparts are just as clearly in a studio) and done on a considerably larger canvas than I have ever seen before with Duvivier.

The film has only one female actor, Ellen Drew and she is competent. As ever the director extracts much better performances from men.

Clement distinguishes himself in service, rising in the ranks to officer level and thus looking very distinguished wearing a Sam Browne belt. Not only is this "interlude" excessively long, it destroys any chance of real connection between the incipient plot of Clement as murderer (even one revealed as having had no real chance at life – of course there has to be some excuse for his crime!) and the denouement of his ultimate exposure and punishment. At the beginning Clement is a man without interest in life and this might be considered reasonable in view of his unhappy upbringing, even if this is simply described by him rather than experienced by us. Whereas Clement derives real purpose and apparent fulfillment in action with his buddies and for "the cause". Yet at the climax of the film, he sacrifices himself in circumstances that may not have been necessary and seem contrary to the enlightenment he has received in service to date. These are infelicities in plot and script which I think would have been corrected were not the director his own producer and scriptwriter.

A major inducement for the director to seek employment in Hollywood was to gain access to the studio system and its infinitely greater resources than those of his home country, France. Within the standards of the time, this is fully shown in the film I saw: the print is exemplary and crisp with clearly delineated gradations of light and shadow. There is only one battle scene, at the climax and perhaps for a film which would have been perceived as a "war film", the general lack of action would have told against audience reaction. That said this climax is exemplary, as least as so far as it concerns the French forces who seemed to be, at least partly in real-life surroundings (whereas their German counterparts are just as clearly in a studio) and done on a considerably larger canvas than I have ever seen before with Duvivier.

The film has only one female actor, Ellen Drew and she is competent. As ever the director extracts much better performances from men.

Certainly not a great

film but eminently worthy of being watched by those committed to this director'

s oeuvre.

Thursday, 26 November 2015

Resurrectio/Resurrection - Barrie Pattison begins a trawl through the work of Alessandro Blasetti

|

| Alessandro Blasetti |

Blasetti is brushed off because his best work is mainly in the void between CABIRIA and the point where (American) critics discovered “Neo Realism” during the post WW2 occupation. He was the man who was responsible for my finding Marcello Mastroianni in his fifties Sophia Loren movies and the director of the first dubbed movie I ever saw - FABIOLA. Suspect qualifications?

On the evidence which is only now surfacing Blasetti was however one of the most interesting film makers of the early years of sound. His take on talkies was different from the work being done around him and much more assured than debut films from China, Portugal, Australia and other out of sight centers. He tells the story in visuals backed by noise and music, only going into synchronized speech when the camera moves in on the characters’ conversations. In RESURRECTIO several of the best scenes are voiceless - the bus ride

and Lya Franca at the Concerto Sinfonia. It is put together with imaginative devices like the reminder visualization of the pistol inside popping on and off her dropped bag, handed back by the beat cop who doesn’t check it, or dissolves between close-ups and the consequences.

|

| Lya Franca & Daniele Crespi |

You can count sound films then as good as this one on a saw miller’s fingers but RESURRECTIO vanished even in it’s home market. Blasetti has been ignored despite his skill and versatility and it takes determination to locate his best work. The fun part is finding it paying off.

Resurrectio, Italy, 1931, 64 minutes. Direction, Script/Alessandro Blasetti, Dialogue/Guglielmo Zorzi, Producer/Sefano Pittaluga, Cines Produzione

Cast: Lia Franca/the girl, Daniele Crespi/Pietro Gadda, Venera Alexandrescu, OLga Capri, Aldo Moschino, Giorgio Bianchi, Aristide Baghetti, Umberto Sacripante, Giuseppe Pierozzi.

Vale Setsuko Hara - Quentin Turnour remembers

Cinephile and archivist Quentin Turnour offers an additional personal thought.

|

| Tokyo Story |

I was never much for her

skills as a an actress, or her essence (Tanaka Kinuyo does it for me in skills

and range, the mysterious Mizukubo Sumiko for essence). But how she came to be

the emblem of Japanese post-war women remains essential in making sense of

that time in Japanese culture and its movies - and their balance-finding

between public ambition and domestic duty, their moments of insistance and

withdraw (... and I still see it just a bit in many Japanese women I know

who work successfully in their film industry now). That's the mystique that

animator Kon Satoshi was trying to explore in his partially biographical

Millennium Actress (Japan, 2001).

And speaking of mystique, of course she

made up a part of what Ozu meant for western fans, beyond the director's

technical skills.

Wednesday, 25 November 2015

Vale Setsuko Hara

A memory.

Alexander Payne burst out of the Jolly Cinema in Bologna way back

in 2013 and said almost to the entire crowd. "My god. Did you see Setsuko

Hara in that movie". The film was Kochiyama

Sochun (Sadao Yamanaka, Japan, 1936). She played a character named Onami.

She is the last person listed in the credits in the Bologna program book and

the accompanying notes by Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordstrom make no mention

of her role or her appearance. Their focus is on the director Yamanaka and the

film's place in the firmament of early Japanese sound films. In the swirl

of a four films a day event I cannot of course for the life of me remember

anything beyond Payne’s exclamatory moment!

It was not Hara's debut, that occurred in Tamerau nakare wakodo yo (Tetsu Taguchi, Japan, 1935) I suspect

not a film that even any of the cognoscenti will have seen.

Her lasting contribution though was made

in the six films she made for Yasujiro Ozu and we should be grateful to the DVD

company Criterion for immediately posting a wonderful essay by the late Donald

Richie titled Ozu

and Setsuko Hara.

Hara had not acted for close to fifty years but she is as luminous

as ever and will so remain.

Defending AFTRS - An update on the Film School's activities prompted by the arrival of the new CEO

In response to a note I sent to the then Arts Minister drawing his

attention to the information contained in the most popular and widely read post

on this website (which you can find here), a Federal

Government official wrote in reply:

“As the national screen arts and broadcast school,

AFTRS continues to adapt to the changing demands of the industry in order to

provide advanced education and training to meet the evolving needs of

Australia’s screen and broadcast industries. AFTRS has been rated as one of the

best film schools internationally and the Australian Government is proud to

support its commitment to nurturing young artists. I note that AFTRS students

have the opportunity for training in all facets of film and television

production and in radio broadcasting, and it is notable that almost all

graduating radio broadcasting students are employed in their chosen field.”

To

make it easy here are some relevant paras from that earlier post:

In the ten years between 1993 and 2002, the

Australian Film, Television & Radio School produced 29 graduates who have

directed 55 feature films.

In the ten years between 2003 and 2012, the School

produced 3 graduates who have directed 5 feature films.

AFTRS began

life as an elite institution intended to find and develop the most talented

would-be film-makers. Much has always been made of that extraordinary group of

young people who were in the first so-called Interim class designed to get the

thing up and moving including Phillip Noyce, Gillian Armstrong, Chris Noonan,

Graham Shirley and James Ricketson. Whoever conducted the search for would be

students did an amazing job. Later years saw a panoply of talent find its way

to the school and benefit from the national largesse involved in training of

the highest order. There was much envy at the resources, physical and

financial, devoted to AFTRS from film schools in the outlying states which had

to battle on with much more limited resources. But such is the way for elite

training institutions.

Among the initiatives for which AFTRS could devote

resources was that for the dedicated training of indigenous film-makers,

initially held in 1991, 1993 and 1994. Over the next seven years AFTRS trained

a whole generation of Indigenous filmmakers including Rachel Perkins, Warwick

Thornton, Ivan Sen, Catriona McKenzie, Adrian Wills, Beck Cole, Steve McGregor

and Darlene Johnson – all of whom were selected for the immersive,

conservatory-type training courses in merit-based competition along with other

applicants.

What was achieved? Well, this

may smack of a bias towards elitism, but what was being aimed at was the

production of film-makers who would make the highest quality films. They would

win international as well as local prizes. They would be invited to the world’s

great film competitions, in Europe most especially, where each year perhaps

fifty films are identified by the international program selectors and endorsed

by the international critical and distribution communities as the best on offer

for this moment of time. This is an expensive process and one fraught with risk

at many steps. A poor or sub-standard faculty, unsympathetic administrators,

reductions in government funding and lots of other external factors can

seriously and continuously blight an institution’s general level of

achievement.

People are now

taking a serious look at just what AFTRS did in the distant past and what it’s

up to now as a new CEO arrives to take charge at a time when the school, from

the start of 2015, apparently headed in a new direction.

I don’t think the Federal Government official’s reply quoted above

really got to the nub of the matter but heck they get a lot of complaints about

everything these days and signing off these things, and in the process

defending the Government and its institutions, is what they are paid to do.

Been there and done that myself.

So.....AFTRS – the here and now.

New CEO Neil Peplow has arrived from the UK and is now part of the here

and now. Since he arrived AFTRS has already been subject to some interesting

recent developments. First of all one thing has been

completed. The departing departmental head Ben Gibson has now been appointed to

run the Berlin Film School and according to a report

in Inside Film has completed

a research project for AFTRS Council documenting the nature and use of screen

Master of Fine Arts degrees. Whether this has already been considered or is to

be considered when a full Council has been assembled is not known.

I should explain that at this time it should be noted

that although AFTRS legislation prescribes that it shall be governed by a

Council of Nine members*, at present it has only five. It has no Chair (Professor

Julianna Schultz has apparently departed after only one three-year term) and

two of the current five members - the CEO and the staff elected rep - are drawn

from the School staff. This is not as a rule the way to manage a major tertiary

institution. Needless to say, no Council Member is raising any sort of public

peep about this situation nor is the Labor Opposition, the Greens, the Clive

Palmer group, Nick Xenophon, John Madigan, David Leyonhelm or Bob Katter to

name forty. AFTRS affairs do not rate highly on the public interest scale.

Those remaining Board

Members are currently unable to take any decisions that might materially affect

what’s happening at the school. However some action has been taken. The School

has posting on its website a survey regarding industry skills and is seeking to

have both companies and individuals respond. AFTRS explains this thus: AFTRS is issuing a call to

employers and professionals across film, TV, radio, VFX, animation,

brand management and interactive sectors to provide insight into the education

and training needs of the screen and broadcast industry.In a constantly

changing media landscape, AFTRS'

Industry Skills Survey will identify immediate priorities as well as

signpost future needs and trends. As the screen and broadcast industries

continue to be disrupted by new technologies and distribution platforms, it is

essential that the necessary skills and talent needed to adapt are identified

and addressed to ensure future growth and innovation.AFTRS is asking for you to tell us what

skills you or your employees need both now, and in the near future. The online survey is quick and simple to complete and AFTRS will

publish the findings in 2016.

So AFTRS would claim it is looking forward.

The essence however of the most popular post ever

published on this blog was that whatever the future may hold, the past

shouldn’t be dumped. The educational protocols that produced such an array of quality

feature film directing talent from inception to around the early 2000s (hard to

put an exact date on it) was overthrown and AFTRS has stopped producing

talented directors able to advance quality film-making in Australia. One statistic would seem to sum up

the major changes wrought at the institution. Until

2007, AFTRS was graduating around 60 per year in Film and Television. Since

2008, the School has been graduating approximately 180 to 250 per year in Film

and Television.

AFTRS is certainly not looking back over its shoulder to examine just

what it might have been doing right or wrong since the early

2000s, the subject of the post mentioned above. But as one harbinger of just

how it sees itself, AFTRS has put up a news

item in which it lists 23

AACTA nominations for AFTRS alumni for their work across film & TV

including Best Film and Best Director in 2015.

So here’s this year’s list of AACTA nominees, taken from the

AFTRS website.

·

Best Film: Sue Maslin (The Dressmaker), Robert

Connolly (Paper Planes)

·

Best Direction: Jocelyn Moorhouse (The Dressmaker)

·

Best Original Screenplay: Robert Connolly, Steve

Worland (Paper Planes)

·

Best Cinematography: Steve Arnold ACS (Last Cab to

Darwin)

·

Best Editing: Andy Canny (Cut Snake), Margaret

Sixel (Mad Max: Fury Road)

·

Best Sound: Alex Francis (The Dressmaker)

·

Best TV Drama Series: Tony Ayres (Glitch)

·

Best Direction in a TV Drama or Comedy: Shawn Seet (Peter

Allen - Not The Boy Next Door Ep 2), Kriv Stenders (The Principal

E 1)

·

Best Screenplay in TV: Jacquelin Perske (Deadline

Gallipoli Part 1)

·

Best Sound in TV: Rainier Davenport, Annie Breslin

(Redfern Now - Promise Me)

·

Best Original Music Score in TV: Antony Partos (Redfern

Now - Promise Me)

·

Best Short Fiction Film: Kelrick Martin (Karroyul)

·

Best Feature Length Documentary: Gillian Armstrong (Women

He's Undressed)

·

Best Documentary Television Program: Jo-anne Mcgowan (Between

a Frock and a Hard Place), Kelrick Martin (Prison Songs)

·

Best Direction in a Documentary: Kelrick Martin (Prison

Songs)

·

Best Editing in a Documentary: Andrea Lang ASE (The

Cambodian Space Project - Not Easy Rock'n'roll)

·

Best Sound in a Documentary: Dan Miau (Life on the

Reef Ep 1)

·

Best Original Music Score in a Documentary: Antony Partos

(Sherpa

Of note however is there are only two nominations

for an AFTRS graduate from the past thirteen years. One is Sue Maslin, producer of The Dressmaker, who successfully completed an AFTRS Master of Screen Arts and

Business in 2013. At that time she was already an established producer with 3

features, 2 feature length docos, 4 docos and 2 shorts under her belt. The

other is Alex Francis, a 2012 graduate who has been nominated for best sound.

Over those thirteen years AFTRS received

Government support of $282.7 million.

*There are nine members of the Council, specified under the Act:

·

three members appointed by the Governor-General

·

three members appointed from convocation by the Council

·

the Chief Executive Officer, ex officio

·

one staff member elected by staff each year

·

one student member elected by students each year.

Monday, 23 November 2015

On DVD (11) - House of Mystery - Alexandre Volkoff and Ivan Mosjoukine's 1921/22 serial

|

| Alexandre Volkoff |

Among the many confessions I have to make about what I have and

haven't seen is that I have seen almost nothing of the work of Alexandre

Volkoff and his collaborator and lead actor Ivan Mosjoukine. Others have known

of them for decades. Earlier this year I got a first glimpse when I watched a

bootleg of their The White

Devil (France, 1930).

Wikipedia has much information on Mosjoukine,

including some most interesting near-gossip that I cant possibly verify but I assume it's

pretty accurate.

Even before I knew

anything of these people MOMA in New York had devoted a season to

Films Albatros the introductory note for which is still on the MOMA website though the essay referred to at the end no

longer seems to be available. A pity.

Even earlier Flicker Alley

issued a DVD box set titled French

Masterworks: Russian Émigrés in Paris 1923-1928, which I now find Dave Kehr

reviewed in glowing terms even before the MOMA season . in his

New York Times video column. It's

hard to keep up.

|

| Silhouette shot from House of Mystery |

Still the emergence early

this year of House of Mystery did set a few pulses racing

including the judges of the DVD competition at Bologna. More attention should

have been paid. Before that had occurred however I now also find that Kristin

Thompson wrote a long essay on the blog she shares with David Bordwell which

you can find here. at

Observations of Film Art /.

|

| Ivan Mosjoukine in House of Mystery |

Here's a key para Like so many of the

major French films of the 1920s, especially the Impressionist ones, La Maison du mystére combines a sentimental,

old-fashioned story with unconventional stylistic devices: unusual pictorial

motifs, beautiful cinematography and design, and imaginative staging. It is

probably this visual interest that led to the film’s original acceptance by

reviewers and to its enthusiastic reception by modern historians and

silent-film buffs.

What

more can I say.